In the lead-up to an Incendiary Traces draw-in focused on San Clemente Island, I have been thinking a lot about historical precedents of drawing San Clemente Island, and by extension, Pacific islands in general. Who drew these islands in the past, under what circumstances, and in what forms? I am surely not the first person to gaze at the Pacific islands and wonder what loveliness must inhabit these islands, close to the California coast, but totally inaccessible except by boat, a few days of sailing and/or a few hundred dollars of boat fuel. And where did the popular idea come from that islands like these might be lovely? My search for precedents of gazing at these islands from afar and drawing them on site (in the European tradition) lead me to European and American imperial and military imagery. Some of the earliest European representations of the Southern California coast and Pacific islands are from imperial Spanish and British expeditions, as well as U.S. Naval activity. My purpose here is to look at the legacy of this landscape tradition and how it may affect our understanding of our Southern California coast and islands.

View of Island of Otaheite (Tahiti), William Hodges, Grey wash and watercolor, 368 x 539mm, 1773 | Courtesy of Trustees of the British Museum | Back Inscription : "A View in the Island of Otaheite from the Land looking towards the Reef & Sea, and which has much the appearance of the Low coral Reef Islands, the Plants a(re) Coco Nut Tree. & Plantain which are indigenous Drawn from Nature by W Hodges in Year 1773"

As Janet Owen Driggs shows in her essay “Even Our Palm Trees Are Cooler,” Southern California was built up in the late 19th and early 20th century upon Anglo conceptions and fantasies of the subtropical environment here. And as Susanna Newbury shows in her essay “How a 19th Century Painting Transformed California’s Desert World,” railroad companies, real estate boosters, the US Geologic Survey and others relied upon the European landscape tradition in painting to establish views of the west for purposes of selling the area to the east, as it was “manifest destiny” to establish an official Anglo U.S. foothold in the area. While these essays focus on landscapes of the interior, they indicate the significance of Anglo landscape ideals and images, largely driven by expansionist initiatives, in shaping Southern California. To further this investigation, I look here at the resonance of early European imperial and U.S. military views of the coast and Pacific islands. I focus on naturalistic images recorded by artists who viewed the subject first-hand, as well as maps. Both forms were driven by the topographic imperative, that is, to present how a place would appear to viewers if they were there themselves. The images I found point to a history in which forms of landscape imagery we have come to take for granted as realistic, accurate and authoritative, have historically been instrumental in creating popular myths about Pacific island paradises, as well as commercial and military visual information used in the expansion of European empires, and later, U.S. territory. This post provides a selection of materials for consideration: 17th century maps of the Spanish views of the Southern California coast, 18th century British landscapes illustrating the Polynesian Pacific Islands, and 19th century watercolors of the lower California coast drawn by an American Naval officer serving during the U.S.-Mexican War. The selection reflects my artistic research on this subject, which is perhaps idiosyncratic rather than an art historical survey. Also, these images were on my mind as I went out to draw our own Pacific island paradises (or at least natural refuges) in the southern Channel Islands during my own “draw-in” expedition to San Clemente and Catalina Islands. (Read my report on that event here.)

Spanish Maps

Map of California shown as an island, Joan Vinckeboons, 1650 | Courtesy of Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress

As early as the 16th Century, chronicles of European expeditions to the Pacific were illustrated and mapped to collect information for military and commercial purposes. Among the earliest visual documents of Southern California’s Pacific region are maps drawn from the expedition of Sebastián Vizcaíno, a Spanish nobleman, explorer and merchant who embarked upon the Pacific in 1602. Charts of Vizcaino’s vision of the coast were considered authoritative for almost two hundred years after his voyage; they continued to be used until about 1790. Although Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo was the first known European to explore the California coast sixty years earlier, Vizcaino’s accounts of his voyages popularized the names used to identify the area, including San Clemente and Catalina Island. Though Spain was the first European empire to record and map the Pacific coast, visual materials were most often created off site by artists who worked later, back in Europe, from primarily textual accounts without having seen the places they illustrated. The results were speculative and often inaccurate. For example, the map of California as an island often published today to illustrate Spanish imperial (mis)understanding of the region was drawn by Johannes Vingboons (aka Joan Vinckeboons), who worked from mercantile and military surveys to create this map for the Dutch West India Company. These maps were considered military and commercial intelligence, and therefore went unpublished until centuries later. Views of the Spanish Empire in the Pacific region thus had little opportunity to seep into the broader European collective imagination.

British Imperial landscapes of the Pacific

View of the Islands of Otaha (Taaha) and Bola Bola (Bora Bora) with Part of the Island of Ulietea (Raiatea), William Hodges, Oil on canvas, 345 x 516 mm, 1773 | Courtesy of National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Ministry of Defense Art Collection

The first naturalistic representations of the Pacific created by artists actually aboard ships were made on British Captain James Cook’s expeditions from 1768 to 1780. In his book Imperial Landscapes: Britain's Global Visual Culture, 1745-1820, John E. Crowley notes that William Hodges was the first professional landscape artist in the Pacific. He quotes a letter from the Admirality directing Hodges to “make drawings and Paintings of such places in the Countries you may touch at in the course of the said voyage as may be proper to give a more perfect idea thereof than can be formed from written descriptions only.” Crowley explains that the timely and wide publication of these landscapes popularized these British views of the Pacific as the premier European perspective and enfolded these areas into the British empire culturally, if not by military conquest. (To maintain diplomatic relations with the Spanish and French, Cook was specifically instructed not to intervene militarily and to conduct himself only as an observer/visitor.) Earlier Spanish views of the Pacific like Vizcaino’s were only published after Cook’s expeditions began to have this affect. The fact that the British landscapes were firsthand visual accounts reinforced their authority. Though Cook’s expeditions were in the Polynesian islands, not the California coast, the Anglo views of the Pacific may have laid a foundation for the Southern California fantasy we know today.

It is interesting to note the palm tree figures in this imperial imagery, which appears to be an origin of the Anglo ideal of the palm dotted island paradise. As well, the palm tree was used by early Anglo Southern California boosters to fashion the region as an idyllic paradise. (See Janet Owen Driggs essay for example. Though Owen Driggs refers to the subtropical environment, and Cook explored tropical regions, the Anglo ideal of the palm tree dotted landscape overflowing with bountiful uncultivated fruits, basically free and easy food, was widely publicized in Captain Cook’s accounts. He wrote in some detail about his gustatory explorations while on his Pacific expeditions, including detailing the bounty of fruits in the region.)

William Hodges, View from Point Venus, Island of Otaheite, Oil on panel, 240 x 470mm, 1773-4 | Courtesy of National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK

Conway Shipley, Papeiti Bay Tahiti, Lithograph, 1851 | Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

But what about California? Did the Brits do their imperial landscape magic there? Captain Cook didn’t make it to California. The closest he got was the Pacific Northwest. (A map of his routes is here.) However, it is clear that the images produced on his expeditions and later published made a large impact in promoting the popular image of the Pacific, which continues to resonate today. Crowley notes that 2000 copies of Cook’s account of his first Pacific expedition were printed, followed by 2500 additional copies a few months later. The Bristol Library circulation records show this was the most checked out book if its time. As Geoff Quilley suggests in his essay “Re-enacting Art and Travel”, Hodges’ palm-dotted paradise image established a foundation for the Anglo collective understanding of what the authentic Pacific looks like. Hodges imagery was “re-enacted” on subsequent British explorations, that is, recalled and mimicked by later British explorers in writing and imagery, as they imagined their authentic experience of these Pacific islands should look like the vision Hodges painted. Now “re-enacted” from travel brochures to upholstery fabric design, this Anglo perspective was grafted upon Southern California as early as the 19th and early 20th century.

U.S. American

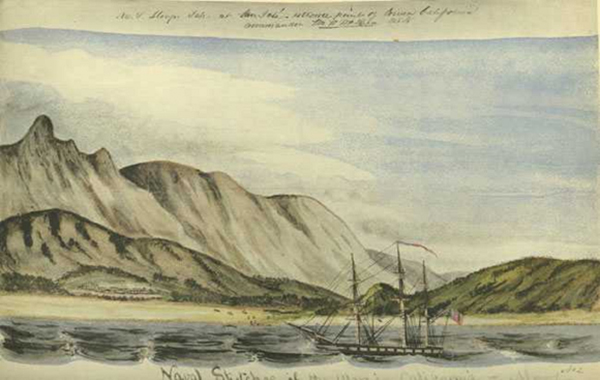

William H. Meyers, The USS Sloop Dale off La Ligas Rocks (27 November 1846), from "Naval Sketches of the War in California", Watercolor Print, Limited Edition of 1000, Grabhorn Press, San Francisco, 1939 | Courtesy of Franklin Delano Roosevelt Collection

So who did make it to Southern California to draw its coastline in this naturalistic tradition? Examples of this tradition of visually documenting the first-hand experience of the Pacific landscape, employed so skillfully by the British, are found again later during the US-Mexican war. A U.S. naval officer aboard the USS Dale created somewhat simplistic, naturalistic landscapes and coastal profiles to document and depict the battle activities from the perspective of the ship. These images are some of the only ones I found from the pre-photographic era which use the naturalistic landscape gaze similar to the style of British exploration of a century early and contemporary to this American Naval artist. However, the images were not published until almost 100 years later, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt obtained them for his private collection. They were published in 1939 by Grabhorn Press, a publishing house in San Francisco.

Draw-in

The examples cited above demonstrate a variety of ways in which the Pacific landscape was recorded and engaged from an imperial, naval perspective. First hand, naturalistic views played an instrumental role in establishing British imperial power in the Pacific during the 18th Century. Though the British were not the first to explore the area, political decisions to keep accounts of their findings and explorations secret eventually handicapped other countries with claims to the land. First hand naturalistic accounts in the form of drawings, paintings and engravings provided a lens through which to understand unfamiliar places. These images were used to consider commercial and military interests, make decisions, and craft strategies and policies. For the larger public, they connected people to distant lands which seemed remote, yet played fundamental roles in shaping the material cultures and political conditions they lived in. It is this tradition of visual documentation as an instrument of power that Incendiary Traces recalls and considers through the draw-in events. In two weeks, we will report here on the recent draw-in focused on San Clemente Island Naval Weapons Testing Range. Stay tuned for a contemporary view of that island from the waters around it as we painted and drew on a sport fishing boat, while sport fishermen told us about co-existing with the U.S. Navy.

William H. Meyers, The USS Sloop Dale of San Jose off the extreme lower point of California (18 November 1846), from "Naval Sketches of the War in California", Watercolor Print, Limited Edition of 1000, Grabhorn Press, San Francisco, 1939 | Courtesy of Franklin Delano Roosevelt Collection