In 1949 the desert landscape of Indio, California, now home to the Coachella Music Festival, served as a backdrop for a quite different event. Several high school-aged girls from the surrounding area met at a county fair to see which one of them would make the transition from pageant princess to queen. Instead of swimsuits and evening gowns these young women were dressed as visions of harem girls, with bare-midriffs and billowing pants. The stage behind them featured Middle Eastern architecture, a fantasy setting called the "Old Bagdad Stage." Before the winner, aptly tiled Queen Scheherazade, was announced a "recording brought from Algiers of a muezzin calling Mohammedans to prayer" played on the loudspeakers.1 With its Arabian theme, the 1949 Riverside County Fair and National Date Festival serves as a startling example of American perceptions of the Middle East, perceptions that held center stage in the deserts of Southern California throughout much of the 20th century.

Queen Scheherazade and court from cover of Riverside County Fair and National Date Festival Official Program, 1975

With our nation's current political and pop cultural relationship to the Middle East marked by negative stereotypes, the idea of celebrating Arabia, albeit with the disquieting use of the Muslim call to prayer, may come as a shock to many. But the towns in the eastern side of the Coachella Valley, just over 125 miles from Los Angeles, have long utilized romanticized portrayals of the Middle East to shape views of their own desert backyard. Recently, Incendiary Traces visited mock villages at Southern California's Twenty-nine Palms Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center, villages designed to train soldiers for combat in the Greater Middle East. I hope to shed light on some of the other connections to the Middle East our desert region has constructed over the past century. Those who used fantasies of the Middle East as a form of boosterism in Southern California did so with the hope of promoting the unique ties the areas shared -- the imported date fruit industry and the desert landscape -- to sell the crop, the land, and tourist experiences.

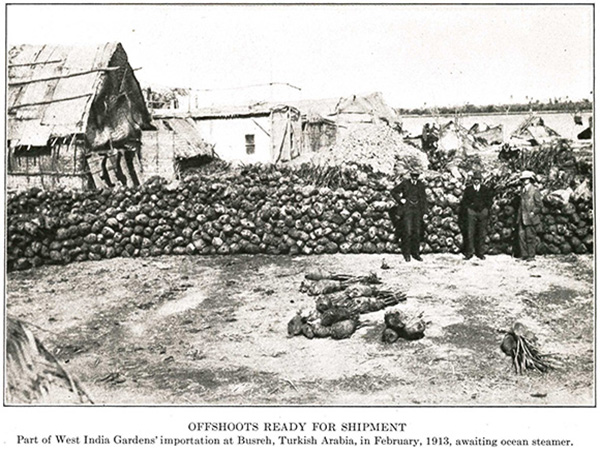

From Paul B. Popenoe, "Date Growing in the Old World and the New", West India Gardens, 1913

As one of the first and oldest domesticated crops, the date palm has a long history in the Middle East and Northern Africa. Although a few date palms were planted by the Spanish Missionaries during the late 1700s, few trees in the Golden State produced much fruit. Though some Americans were able to obtain imported dates before 1900, as a whole the fruit and its cultivation remained a mystery not only to consumers but also to agriculturalists. At the turn of the 20th century, the United States Department of Agriculture encouraged the development of new crops throughout United States, and dates were of interest. However, in order to create a commercially viable date industry, date offshoots from the Middle East and Northern Africa had to be imported.

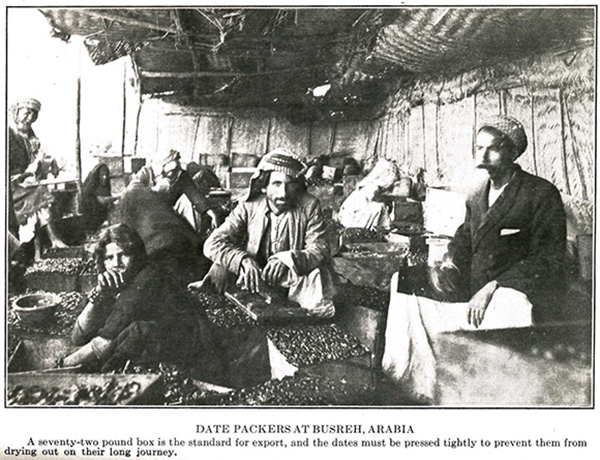

From Paul B. Popenoe, "Date Growing in the Old World and the New", West India Gardens, 1913

After the railroad eased transportation through the deserts of Southern California in the late 1870s, non-native settlers arrived in the region hoping to utilize the area's rich soil and artisanal wells. The cities around the railroad station in Indio, California began to grow vegetables and fruits. As this "reclamation" project progressed, the Coachella Valley received the attention of several scientists who thought that dates could be commercially grown in this desert region. Several of the USDA's "agricultural explorers," a breed of government scientists who sought new crops from around the world, were sent to Algeria, Iraq, and Egypt at the turn of the 20th century. These explorers brought back date offshoots, planting these young palms in experimental stations throughout the desert Southwest, including in Tempe, Arizona and the Coachella Valley. When local entrepreneurs saw government interest in the fruit, a few even made the trip to the Middle East or Northern Africa themselves, bringing back their own offshoots to sell or plant. To the delight of the USDA, the deserts of Southern California proved the perfect place to start a new, and largely profitable, agricultural industry.

Details from Bruce Drummond's "Propagation and Culture of the Date Palm", USDA's "Farmers' Bulletin 1016", 1919 | Courtesy of Hathi Trust

These trips to the Greater Middle East for the date palms provide some of the first links between the two regions. The interactions these government scientists and local entrepreneurs had with the people of the Middle East are extraordinary and they speak not only to the complicated geopolitical realities of the area but also to American assumptions of racial and scientific superiority. One Los Angeles Times article about the growing date industry, published in 1921, suggested that the "American scientific culture has far surpassed the Orient in date possibilities. In fact in the hot sand around Indio and Coachella the date has come to surpass anything of which the dozing Orient ever dreamed."

From Paul B. Popenoe, "Date Growing in the Old World and the New", West India Gardens, 1913

Sometimes the trips abroad even got Americans into hot water. One Altadena based nursery, the West India Gardens, sent two young brothers, Paul and F.W. Popenoe, and a few associates to the Persian Gulf and Algeria to obtain over 15,000 date palm offshoots between 1912-1913. They brought back with them not only the date offshoots that would start the burgeoning industry but also fantastical stories that played into American perceptions of the Middle East as a romantic yet occasionally dangerous place. One Coachella Valley news article, "Date Trees Come Stained with Blood," suggested these young men, who were under the protection of the Sultan of Oman, were attacked by forces who opposed the Sultan.3 Though the young men claimed to instigate a civil war while trying to obtain dates for their family nursery, one might also suggest they were mere pawns in local political struggles the Americans had little understanding of. This rich origin story of the local date industry at once praises Arabia, with the Sultan offering the young men protection, friendship, and his best camel, while also creating a romance around the danger of traveling to this exotic place, a location seldom traveled by Americans of the era.

From Paul B. Popenoe, "Date Growing in the Old World and the New", West India Gardens, 1913

Before long the date industry took root in the Coachella Valley and local farmers also became local boosters. These farmers sought not only to sell their dates but also to market the lifestyle of a date grower, a goal supported by scientific knowledge from the USDA's experiment stations and scientists who shared their expertise with the nation's farmers. The Southern Pacific Railroad also functioned as a backer, seeking to encourage development in the Coachella Valley that would foster tourist travel, expand land sales, and perhaps increase railroad usage by future farmers. These local boosters heralded the profits of date growing to anyone who would listen. They quickly turned to the romance of Arabia to put their small towns on the map.

From "The Sunset Route and Scenic Wonders of Arizona from El Paso, Texas to Los Angeles, California via the Southern Pacific", Van Noy-Interstate Co, 1921 | Courtesy of Braun Research Library, Autry National Center

Pamphlet distributed at the Panama Pacific International Exposition (World's Fair) in San Francisco, 1915 | Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California

Putting their region on the map meant renaming some of their towns. In 1904, the town of Walters -- named for an early settler in the region -- was renamed Mecca. Rumor has it that Mr. Walters was none too happy with the name change. In 1913, a new city in the Coachella Valley launched as "Arabia". But Arabia was more than a clever name. The land and water company that sought to develop it had plans to create a city that looked as if it belonged in the Middle East, as "the style of the buildings and the general appearance of the town would be oriental."4

Despite the big plans and local press dubbing it the "most unique city in America," Arabia was abandoned in the 1930s with few, if any, remnants marking the location today.

Long's Palm Ripened Deglet-Noor Dates from the Coachella Valley Pamphlet, 1948 | Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California

Exhibitions at San Bernardino Agricultural Expo, undated | Courtesy of Braun Research Library, Autry National Center

Even more startling were the plans made in the late 1920s for an Arabian-themed hotel and shopping complex where guests would arrive via camels and walk among architecture reminiscent of the Sahara. The Walled Oasis of Biskra, named after the well known Biskra of Algeria, took its inspiration from native palm trees that grew in oases in the Coachella Valley. (See the location, with "Arabian" tents here.) Though the Walled Oasis of Biskra seems to fit perfectly in the Southern California fantasy landscape that also houses Olvera Street and Disneyland, travelscapes where you can visit the world without leaving the state, it was not to be. Going bust with the Great Depression, the Walled City did not appear to move forward with building, though one wonders what happened to the camels that were purchased by its founder.

"Guests at California's Biskra who arrived on Camelback" from Charles H. Jonas, "The Walled Oasis of Biskra: An Interpretation of the American Desert in the Algerian Manner", Hoag and Ford Advertising, circa 1928 | Courtesy of the San Diego Public Library

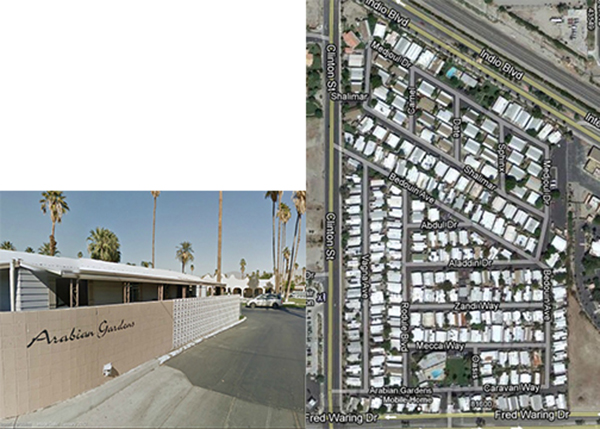

References to the Middle East go beyond city names in the Coachella Valley. Visit Indio or Coachella today and you can drive down streets named Arabia, Baghdad, Degelet Noor, Medina, Damascus, Araby, and Camel. You can even visit a high school with an Arab mascot. When visitors from Saudi Arabia saw the mascot in the 1980s, they suggested that the mascot's headdress be changed from a fez, a symbol of French rule, to a ghutrah -- the modern headdress worn in Middle Eastern countries today. The student body voted to approve the change, which is reflected in the images you see. Thus even though much of the "Arabian" images utilized in the Coachella Valley were based in fantasy, locals were occasionally made aware of the changing politics of the countries that they borrowed from and responded with changes to their own image as well.

Left: Mural from Coachella Valley High School | Photograph by Amanda McCormick; Center & Right: Images of Coachella Valley High School's mascots through the years with the current mascot in green. | Courtesy of the Coachella Valley Alumni Association. Learn more here.

"Arab Marching Band" from the Coachella Valley Union High School Yearbook, 1953 | Collection of the author

As the Coachella Valley grew it sought to capitalize on the tourists who came seeking sunshine. Unlike other regional cities that filtered Spanish Colonial history through the romance of sultry senoritas, pious priests, and crumbling missions, Indio and its neighbors sought instead to play up their unique desert landscape by linking themselves to the Middle East. Leaving the red tiled roofs behind, visitors to the Coachella Valley could purchase dates in a pyramid shaped or Arabian inspired stand and the Arabian inspired store, see an "authentic" Bedouin living tent, or visit "King Solomon" -- a male date palm used to pollinate over 400 female palms annually. They could hear a presentation about the "Romance and Sex Life" of a date and pick up a famous (and delicious) date shake. While this type of agricultural tourism was not new, it did have a unique spin that played up the region's agricultural and climatic links to the Middle East and North Africa.

Date mural detail at the corner of Miles and Oasis in Indio, California | Photograph by Margo McCormick

Left: Arabian Gardens Trailer Park in Indio, California. Note the Arabian inspired pool house in the background; Right: Map of Arabian Gardens Trailer Park in Indio, California. Note the Arabian inspired street names like Aladdin Drive and Bedouin Avenue. | Screen shots from maps.google.com

Left: Intersection of Date and Cairo Avenues in Coachella, California; Right: The current Desert Fresh, Inc. building off of Highway 111 and 9th Street in Coachella, California (Formerly Imperial Irrigation) | Photographs by Margo McCormick

By 1921 with the industry ripe for attention, Indio launched its first official "International Festival of Dates." The event, featuring women in Persian costumes and men dressed as Sheiks, sold itself exclusively through ties to the Middle East, as the image below so vividly illustrates.

First International Festival of Dates Pamphlet, 1921 | Courtesy of the Coachella Valley History Museum

Though the fair had sporadic appearances until it became an annual event in 1947 it continues to today. (This year's festival is February 15-24.) The fairgrounds have featured Middle Eastern inspired architecture, a nightly "One Thousand and One Arabian Nights" theatrical pageant presented on the "Old Baghdad" stage, camel races, and a Queen Scheherazade scholarship pageant. Community members were encouraged to dress in costume, especially during the 1940s through the 1960s. Had you visited the Coachella Valley in 1950 you may have been served by a waitress dressed like a harem girl, seen a film in the Aladdin Theater, presented your money to a bank teller in a fez, or seen women's clubs meet entirely in costume.

Undated Postcards of the Date Festival | Collection of the author

Advertisement for Alphy's Family Restaurant from the Riverside County Fair and National Date Festival 1975 Official Program | Collection of the Author

Advertisement for the Indio Municipal Golf Course from the Riverside County Fair and National Date Festival 1975 Official Program | Collection of the Author

Left: Camel and rider from the 2010 Date Festival Camel Races; Right: Sand Sculpture from the 2011 Date Festival. | Photographs by the author

When the date industry began to grow in the 1910s and 1920s the nation held dear the idea of a mythic Arabia as an exotic place of wealth, leisure, magic, and sex. As scholars have pointed out, Americans absorbed the Middle East throughout much of the 19th and early 20th centuries through imperial popular culture; reading about it in the widely popular "One Thousand and One Arabian Nights" or seeing its romance on the big screen, especially as Rudolf Valentino's The Sheik became a blockbuster film. Consumer and visual culture played a role as Arabian scenes displayed wares at department stores and magazines ran ads with Middle Eastern imagery. Fraternal organizations, including the Shiners and Masons called upon the mysteries of Arabia in their rituals. Real and armchair travelers longed to see the Greater Middle East, with travel literature and magazines selling well, while four million viewers saw Lawrence of Arabia slideshows worldwide. The discovery of King Tut's tomb in 1922 unleashed an Egyptomania in the states that could be seen through the creation of Egyptian style theaters and even Egyptian inspired fashions. Notably, religion played a crucial role in American understanding of the Middle East as biblical stories left American Christians imagining the romantic history of the Holy Land.5

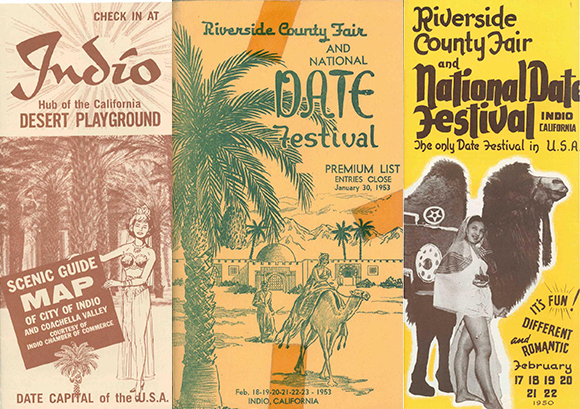

Left: Indio Scenic Guide Map, circa 1975; Middle: Riverside County Fair and National Date Festival Premium List, 1953; Right: Riverside County Fair and National Date Festival Pamphlet, 1950 | Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California

Date Festival Publicity Shot, 1958 | Courtesy of Ivan Henry at The Circus Blog

Left: University of California Agricultural Extension Exhibit at the 1948 Date Festival; Right: Costumed men and Queen Scheherazade contestant at the 1949 Date Festival | Collection of the author

After World War II America's views of the Middle East and Northern Africa turned increasingly to discussions of homelands, oil, and geopolitics. Eventually, especially after the oil embargos and the hostage crisis of the 1970s, popular representations would be dominated by images of terrorism and eventually war. This shift across the twentieth century makes the continued use of Arabian imagery in the deserts of Southern California even more striking. These landscapes -- both the natural space of the desert and the manmade landscapes of agricultural date groves, ornamental plantings, and pyramid date stands -- are spaces that tie us to the Greater Middle East in ways vastly different than the politics of the past 20 years. Yet in some ways they will always speak to American action abroad. The land and the crops themselves have been shaped by years of European and American economic and political involvement in the region, filtered through centuries of popular culture that make most of what is seen in the Coachella Valley a reflection not of the real Middle East, but the imagined one. But even in these spaces that sought to celebrate the connections, however mis-imagined, war and politics have been present. During World War II, General Patton trained troops in the deserts outside of Indio preparing for combat in Northern Africa. And as February's Incendiary Traces Draw-In visits mock villages at the Twenty-nine Palms Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center, we see that the training continues.

Arabian Nights Pageant at the 2012 Date Festival | Photograph by the author

Walled Oasis of Biskra in the Coachella Valley (Click to scroll through a digital copy of the document.)

Notes:

1. Colorful Midwinter Date Festival Opens," The Los Angeles Times, 19 February 1949.

2. "To Revel Date Secrets," The Los Angeles Times, 22 October 1921.

3. "Date Trees Come Stained With Blood" Coachella Valley News and Indio Index, 23 May 1913.

4. "New Town Arabia is Launched," Coachella Valley News and Indio Index, 9 May 1913.

5. For more information on American's popular culture interactions with the Middle East prior to World War II see Susan Nance, How the Arabian Nights Inspired the American Dream 1790-1935. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).