Point Mugu is one of the most spectacular wilderness landscapes in California. From the bluffs off the Pacific Coast Highway in Malibu, hikers are afforded sweeping views of the Pacific Ocean and the Santa Monica Mountains. The U.S. Air Force and Navy also enjoy this overlook, but not for its aesthetic appeal.

Point Mugu is home to the U.S. Naval Base Ventura County (NVBC), U.S. Naval Air Warfare Center Weapons Division (NAWCWD) Point Mugu, and the 36,000-square mile Sea Range – the country’s largest military testing range over water. Here, the U.S. and its allies test, launch and track missiles, fly surveillance aircraft and collect data in an airspace that can expand to more than 220,000 square miles.

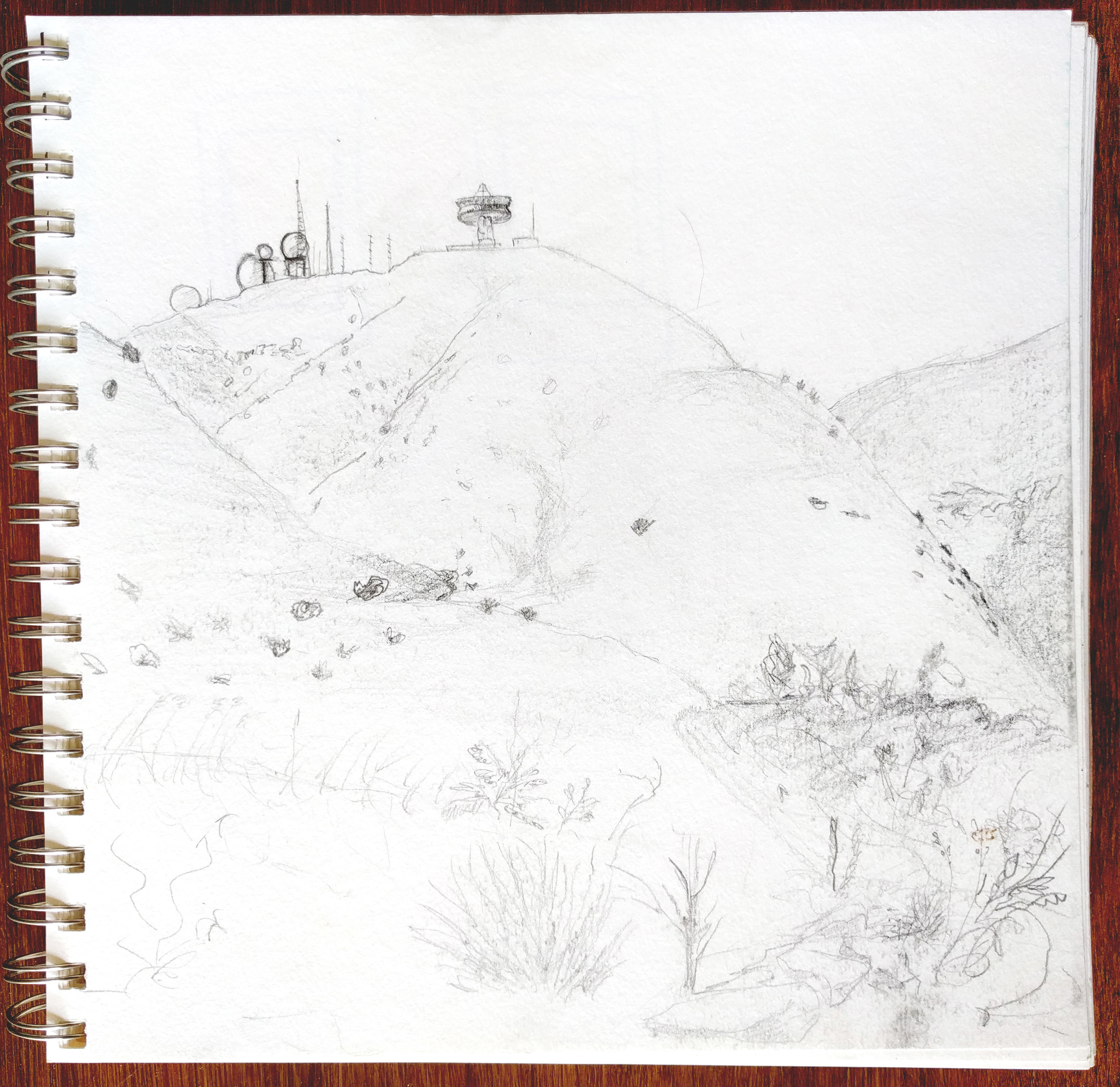

View from Chumash Trail of a shooting range at Naval Air Station Point Mugu | Photo: Jena Lee

Tracking, surveilling and data collecting are ways of seeing specifically tailored to military goals. Last June, we took a group of artists to hike and draw the Laguna Peak Tracking Station at Point Mugu to get a glimpse of the apparatus that enables the military to have a technologically augmented, automated, remote point of view, and consider it in contrast to our comparably low-tech, human, grounded perspective.

The Laguna Peak Tracking Station is one in a network of U.S. satellite stations supporting naval and aerospace missile launches and tracking. The installation is perched on a 1,500-foot-high mountain peak above Naval Base Ventura County (NBVC). It enables military personnel in the Naval Satellite Operations Center (NAVSOC), a control room at the NVBC below, to see and measure the performance of missiles across and beyond this vast range. The technology used at the facility includes coverage of photo and video optics, airborne and surface target control, telemetry, radio communication and data transmission, surveillance radar, and a transmitter system for “Command and Destruct” of intercontinental ballistic missiles.

The NBVC has been at Point Mugu in its current configuration since 2000, but the Navy has been using this site for over a half-century. Naval Air Station Point Mugu was established here in 1942 as a United States Navy anti-aircraft training center during World War II and quickly became the Navy's major missile development and test facility. The base has been home to many weapons-testing programs. The test range extends offshore to the Navy-owned San Nicolas Island in the Channel Islands. In 2000, Naval Air Station Point Mugu was merged with nearby Naval Construction Battalion Center Port Hueneme to form NBVC.

Stages of missile interception by the Arrow system, which has been tested at Point Mugu several times since 2004. The picture shows a hostile missile trajectory and that of the "Black Sparrow" air-launched target missile used in firing tests. | Image Source: Wikipedia

Our visit to the area was part of “Incendiary Traces”, an art, research and media project that involves plein-air reconnaissance missions where groups visit, sketch, and observe local active military landscapes in Southern California and elsewhere. While artists, scholars, journalists, and armed authorities all seek to understand unknown situations, we don’t traditionally use the same techniques or tools to do so. The military relies heavily on specialized technologies and techniques to gain “situational awareness”, and “command” and “control” of the landscape. Given that the military deals with life or death situations, it’s not surprising that they rely on mechanized and quantification-based visualization to impose a sense of objectivity and minimize human error. These technologies can reveal inclinations and occlusions in the cultures that produced them. “Incendiary Traces” draws upon the similarities and differences between the visualization methods of artists, scholars, journalists, engineers and armed authorities to uncover these inclinations.

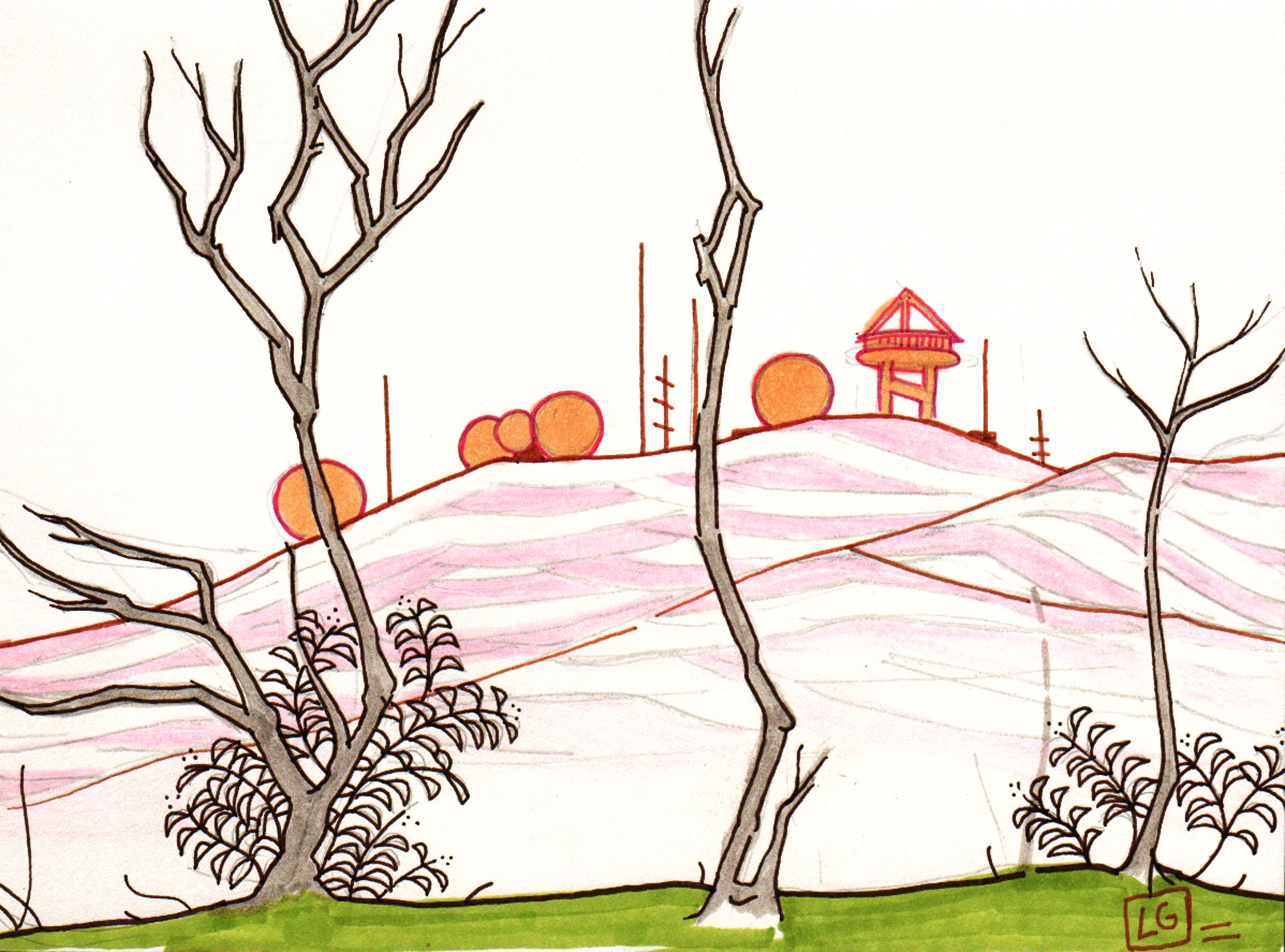

Hillary Mushkin | Sketch of Laguna Peak Tracking Station, 2016 | watercolor and ink on paper

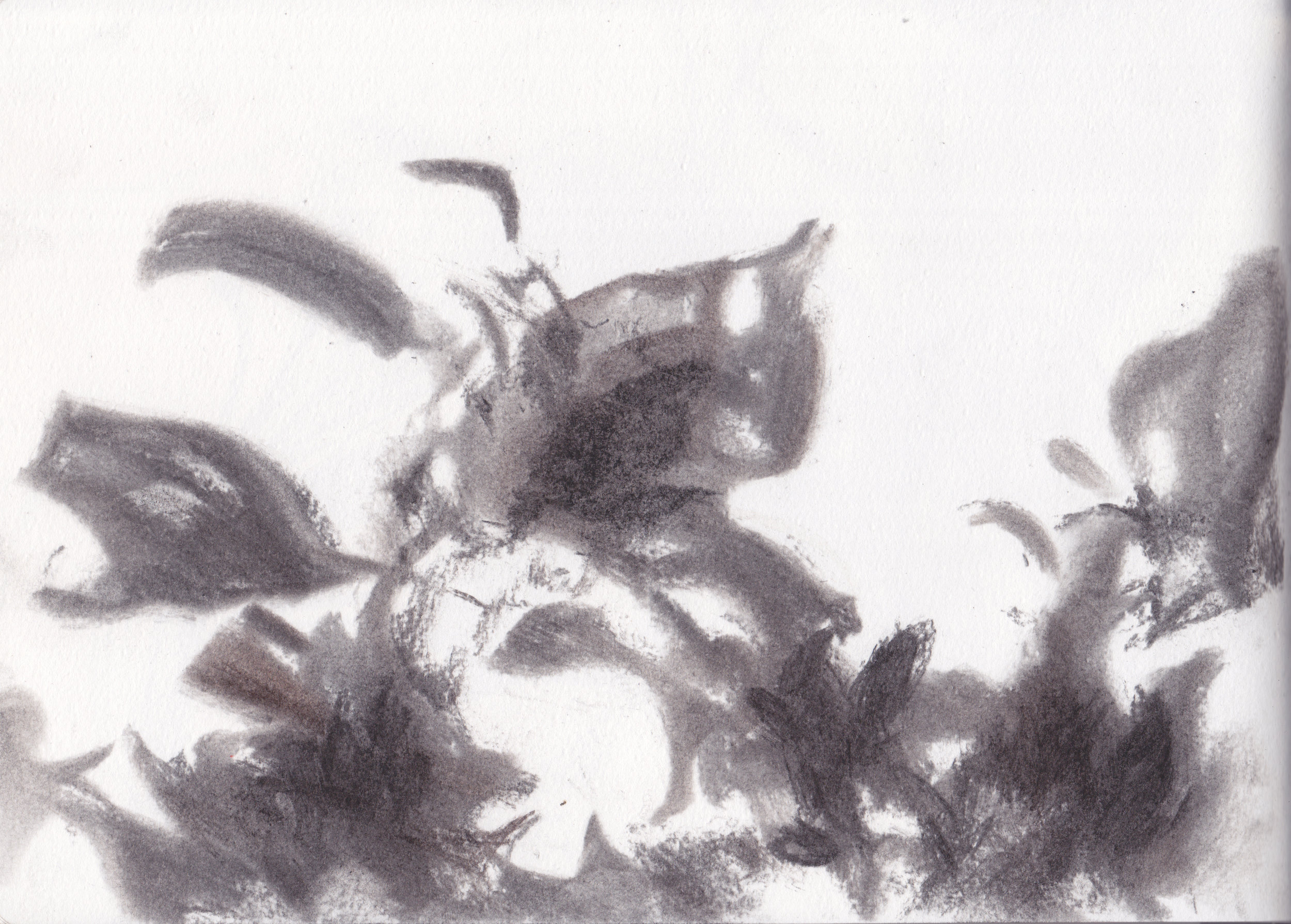

Here, sketches made by the group of artists and writers who joined us that day highlight the significant role human gesture, subjectivity and interpretation play in depicting the landscapes of conflict zones. While we were all looking at the same landscape, our sketches are different. Together, they form a textured, heterogeneous perspective, especially when compared to the centralized view the tracking station contributes to in the NAVSOC control room. Our varied backgrounds and interests reflect what we chose to include in the frame, our choice of medium, level of detail and rendering style.

Joseph Bolstad is primarily a sculptor; his sketch reflects a focus on 3D shape and volume. Hillary Mushkin’s sketch reflects some of the concerns of the larger “Incendiary Traces” project – what we can see from close up, on the ground, and what it is like to look at something from a distance. Working with the fluid, potentially unruly nature of watercolor, she asks, how accurate can a picture be? Jena Lee found beauty and a bit of ironic humor in the contrast between the spectacular rolling landscape and the utilitarian manmade structures. Richard Wheeler’s artistic practice involves research on surveillance and satellite imaging. The photos he made at Point Mugu with a new surveillance scope system he put together show that such technologies can have unexpected results. Conor Collins works primarily with photography and computer graphics. His sketch perhaps reflects a more straightforward attempt to record what he saw. Lesley Goren, an artist who has been studying native flora, chose to foreground the laurel sumac sprouting new growth from a recent fire in the area. Stacie Jaye Meyer was particularly inspired by what was on the ground at our feet. She collected plant material that had been charred in the fire. Her sketches are experiments in capturing the environment using a focal point and methodology that significantly differs from the military’s.

Incendiary Traces is an ongoing project. As technologies that extend perception become increasingly advanced in the hands of those who have the privilege to posses it, this kind of work reminds us of the infinite impossibility of omniscience, and the inevitable persistence of diverse, human perspective.