In the early morning of January 28, 1917, Carmelita Torres, a domestic worker, determined she had had enough and would not stand for the Mexican border quarantine campaign that was to be put into effect that same day. At 7:30am, U.S. customs officials ordered Torres to disembark the trolley traveling across the Santa Fe International Bridge in El Paso, Texas. In assembly line fashion, Torres and others had to file through the newly built El Paso Disinfection Plant where she would be subjected to an intrusive medical inspection, disinfected and sterilized with gasoline. Torres refused to comply and, along with 200 other women from Ciudad Juárez, protested by blocking traffic at the bridge, in effect, temporarily shutting down the facility. Later that week, demonstrators gathered in Juarez to challenge the new medical surveillance measures.[i] After the protests waned, Mexicans and other “questionable” immigrants crossing at the El Paso-Juárez border entry point were then subjected to a delousing and vaccination process that symbolically registered their bodies as vectors of disease. Part of this process required a specific set of medical surveillance practices. United States Public Health Service officials monitored and examined the immigrant bodies that daily crossed the international boundary line. Their medical gaze was overlaid atop a boundary line that both continued older surveillance practices and set in motion new visual sightlines of surveillance.

Fast-forward to today and we find that human patrols, ground sensors, radar, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), and Geographical Information Systems (GIS) make up a few of the surveillance technologies the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) use to detect unauthorized crossings along the more remote and unfenced portions of the line. These tools of surveillance transform the border into a vigilant line of sight, where observational techniques simultaneously create, mark, and read the (in)admissible migrant body. Certainly, the final quarter of the twentieth century into the first decade of the new millennium witnessed an intensification of surveillance by way of an increasingly militarized and technologically sophisticated U.S.-Mexico border.[ii]

However, the drones that hover above the desolate Sonoran desert manned by disembodied video operators, or the stadium lights that currently flood the night, are not unprecedented phenomena. They exist within a longer legacy of border observation and visual representation as technologies of statecraft, as evidenced by Carmelita Torres and the many others who protested against the 1917 Mexican Border Quarantine. It was at the turn of the twentieth century that medical inspection, photographic visual production and documentation, and human patrol ushered in a new set of surveillance procedures for state oversight at the U.S.-Mexico border. This is the story of medical inspection, disinfection plants, and passports. It is a narrative about the emergence of a visual network overlaid an imaginary line during the first half of the twentieth-century, a system in operation long before the digital fingerprint scans and the biometric databases that currently typify our security state.

A decade into the twentieth century, the immigration surveillance apparatus at the U.S.-Mexico border was coming into fruition and slowly refining its ability to identify, mark and exclude inadmissible bodies. This surveillance network came on the heels of emerging forms of visual technologies, increased academic specialization, and western expansion and overseas imperialism, which together fostered a new model of vision, one centered on the primacy of the optical and the ability to “see” racial difference. The professionalizing fields of anthropology, sociology, history, phrenology, psychology, criminology, and medicine all engaged in a budding pseudoscientific discourse that constructed race as biologically immutable and easily mapped racial difference onto the body’s anatomical surface and within its deepest recesses.

Eugenics on the cover of Puck, a humor magazine, 1913 | Library of Congress

California was a hotspot for this type of scientific racism. Its adherents pioneered the eugenics movement, a project that advocated better breeding practices to advance the “best” genes/traits and putatively produce a superior “racial stock.” The Los Angeles Times’ Harry Chandler, Stanford Chancellor, David Starr Jordon, and founder of the Human Betterment Foundation, E.S. Gosney, were a few of the many supporters of the eugenics effort in California. This type of hereditary science merged with calls for stricter immigration restriction at the country’s southern border. C. M. Goethe, member of the Human Betterment Foundation, called on his California representative to consider tighter immigration at the U.S.-Mexico border. Fearful of miscegenation, he asked, “Does our failure to restrict Mexican immigration spell the downfall of our Republic…? Athens could not maintain the brilliancy of the Golden Age of Pericles when hybridization of her citizenry began. Rome fell when the old patrician families lost their race consciousness and interbred with servile stocks.”[i] Following Goethe’s logic, to protect the Anglo-Saxon race required a fortified medical border, which necessarily restricted the undesirable, feeble-minded migrant carrying their adverse genes. This would necessitate a visual apparatus that could sight and process the pathologized mobile body.

In the name of national protection, screening migrants for health maladies became crucial in the management of the U.S. southern border. Late nineteenth and early twentieth century border enforcement centered on the exclusion and racialization of immigrant bodies as a medical and social threat. With scientific advancements in germ theory and bacteriology, public health officials used the medical examination room at border entry points as a means to identify and, in the process, construct the diseased foreigner.

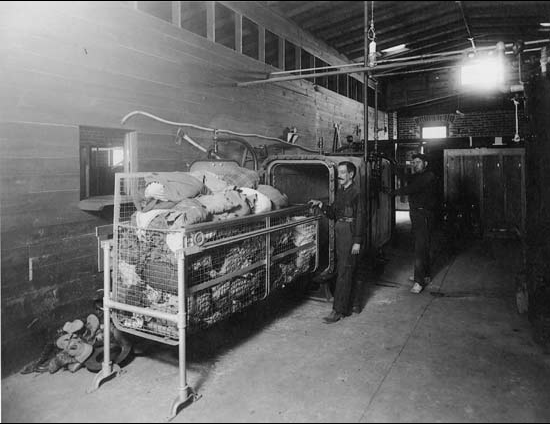

A steam dryer sterilized border crosser’s clothing at the Santa Fe Bridge Disinfection Plant, 1917 | USPHS, National Archives

When it came to tuberculosis, California politicians and health officials in the 1930s pushed for an even more fortified medical border, one that could harness the technology of the chest X-ray. Historian Natalia Molina documents California health officials’ and politicians’ deployment of TB health statistics leading up to and during the Depression as a means to influence immigration policy and enforce a more stringent medical border. The director of California’s Bureau of Tuberculosis, Edythe Tate-Thompson, for example, invigorated the ties between medical progress and immigration restriction. In her data collection, Mexicans accounted for 20 percent of tuberculosis deaths in California. Tate-Thompson attributed the rise of tuberculosis mortality rate to the presence of migrant workers from Mexico. To keep the communicable disease at bay and to minimize the cost of state-funded charity services, Tate-Thompson insisted “for an adequate physical examination of Mexican laborers and their families before entry…and to urge deportation of all aliens who have entered this country and are spreading disease.”[i] Similarly, a state health department weekly bulletin advocated for the “necessary ‘machinery’ to adequately examine Mexicans crossing the border.”[ii] For Californians like Tate-Thompson, an organized medical border with “necessary ‘machinery’” would be a step toward a hard line of defense.

While Edythe Tate-Thompson had called for “adequate physical examinations” in the 1930s, almost fifteen years earlier a medical inspection center was already in operation in Texas and patrolling for the “pathologized” migrant body. Erected in 1917, the El Paso Disinfection Plant processed an estimated 2,830 bodies a day, or 236 per hour. It was a site where immigrants underwent a compulsory medical inspection that included delousing, showering, clothing sterilization, and a “cursory psychological profiling,” directed through a medical assembly line for faster processing.[iii] Claude C. Peirce, a senior surgeon with the United States Public Health Service (USPHS), was the ringleader for what he called the “iron-clad quarantine” at the U.S.-Mexico border. Peirce’s public health service exhibit—his “dioramas, charts, and mechanical displays”—at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, California came to life a year later in El Paso. His techniques for eradicating the transmission of disease were implemented in observational practices in the disinfection plant. The city’s acting assistant surgeon informed the Secretary of Labor that both “appearance and ‘class status’” determined who endured the medical line inspection. One border crosser, José Burciaga, recounted the intrusive quarantine inspection, noting “when someone entered they doused him with something. What a nightmare! And then there was more: men, women, they shaved everyone…they bathed everyone, and after the bath they doused you with cryolite [sodium aluminum fluoride], comprised of some sort of substance, it was strong.”[iv]

Plans for the El Paso Disinfection Plant, 1916 | USPHS, National Archives

Alexandra Stern explores the scientific eugenic discourse and public health practices that informed the construction of the El Paso quarantine station. She argues that the disinfection buildings were units responsible for documenting, enumerating, and classifying bodies. These architectures made the border crosser configurable and controllable through direct observation. Entrance into and movement through the disinfection plant had the potential to transform a questionably diseased migrant into a “desired laborer” or vice versa. The disinfection edifice, the medical surveillance structure, illustrates the city of El Paso’s visual network over the geographic landscape and upon the subjects that crossed over the U.S.-Mexico border.

Visual medical inspections coincided with the state’s implementation of photographic documentation in the form of visas and passports. Historian Ann Pegler-Gordon examines how photography shaped and sustained racialized systems of visual regulation in immigration policy. Late nineteenth and early twentieth-century scientists and state officials invested in the burgeoning practice of photography with the seeming ability to capture objective reality. U.S. immigration policies subsequently managed and observed mobile populations through a racialized system of visual regulation. This narrative first begins at Angel Island, a border entry point at the San Francisco port, whose innovations then traveled south to the U.S.-Mexico border.

Immigration station, Angel Island, California, 1915 | Library of Congress

In the late eighteenth century, the U.S. Bureau of Immigration required Chinese immigrants at Angel Island to provide photographic documentation as proof of their legitimacy to enter the United States. Notably, no similar policy was enforced for European immigrants at Ellis Island on the East Coast. Because Chinese migrants were already racialized and sexualized as cunning and immoral, immigration officials used photographic documentation as a means to limit fraud among the “criminal” Chinese. The Bureau reasoned that photographs could distinguish between admissible and inadmissible Chinese bodies because these images could reveal the respectability or the criminality of the applicant. Chinese migrants who attempted to enter the U.S. as paper sons, or the fictive children to Chinese U.S. citizens, manipulated the Bureau’s mandates for photographic evidence. Migrants did this in a variety of ways: changing photographs on identity certificates, using their own photos to illustrate their falsified paper relationship, and exchanging photographic certificates across different “paper sons.” Pegler-Gordon writes that these Chinese “oppositional practices raised significant questions about the reliability of the photographic image as documentary evidence.” Chinese migrants molded certain identities and subjectivities by undermining the primacy and authority of the visual image.

Chinese "passing" as Mexican, 1907 | National Archives

As public health and immigration officials increasingly rejected Chinese migrants at coastal ports of entry, this excluded group made their way to the southern U.S. border. Immigrant Inspector Marcus Braun obtained visual evidence that Chinese migrants were falsifying their U.S. immigration documents by having their studio photographs taken in Mexico City. The portraits taken were intended to make the Chinese appear Mexican and therefore admissible as legal border-crossers. Pegler-Gordon suggests that Braun included images in his report “to show how in some cases it would be difficult to distinguish these Chinamen from Mexicans.” She further argues that such portraits take on a different valence at the border where they were not used to evade exclusionary laws but to “pass” as Mexican in order to secure entry.[i] In this context it was not manipulation of the image but an alteration of the racial identity in the image as a strategy for visual disruption and passage.

Pegler-Gordon further maintains that the use of photographic documentation to regulate and exclude Chinese immigrants at the U.S.-Mexico border set a precedent and normalized the passport photograph as a standard for entrance into the United States. The year 1917 not only marked the opening of the El Paso disinfection plant, but also commenced a “system of photographic identity cards to monitor [the] movement and employment ” of Mexican border crossers. This incipient system of documentation was implemented regionally in the Southwest due to agribusiness and other U.S. employers’ demand for Mexican labor. By 1924, however, immigration law required visual documentation from all immigrants entering the nation’s borders. The criteria included a visa packet, which contained a “valid passport, a certificate of medical examination, two unmounted passport photographs,” a birth certificate and other state or military records. The photograph became an essential pillar in a new visual system of observation after 1924; towards an expansive apparatus of documentation and immigration control.

The surveillance technologies we see operate and experience today along the U.S.-Mexico border belong to an extended historical legacy of observation and documentation. Race, class, gender, corporal ability and disease informed the construction of either the permissible or aberrant immigrant body at the turn of the twentieth century. As a federal entity, the U.S. border patrol devised various strategies to visually identify and document the mobile bodies that traversed back and forth past an imaginary line. Medical inspection and photography were two instrumental methods in the production of the U.S.-Mexico border in the first few decades of the twentieth century. The racialized threat of the tubercular or the typhoid immigrant body laid the building blocks for a fortified medical border. The better breeding eugenics movement called for intensified medical screening as a fundamental part of the international boundary line. The desire to limit Chinese immigration established a visual system of documentation, which has carried over into its current passport form. However, Carmelita Torres, the border quarantine protestor who began this story, as well as the Chinese immigrants who troubled the evidentiary validity of the photograph, challenged the intrusive medical border sightlines and exposed the state’s own blind spots. The border continues to be a space where new visual practices of surveillance are tested, implemented, undermined and challenged.

For more information on David Starr Jordan in Texas and California see Alexandra Minna Stern, “Buildings, Boundaries, and Blood: Medicalization and Nation-Building on the U.S.-Mexico Border, 1910-1930,” Hispanic American Historical Review, vol. 79, no. 1, (Feb., 1999), 58-60, 75. Additional information on Goethe can be found in Alexandra Minna Stern, “Buildings, Boundaries, and Blood: Medicalization and Nation-Building on the U.S.-Mexico Border, 1910-1930,” Hispanic American Historical Review, vol. 79, no. 1, (Feb., 1999), 75-76. For works on the construction of the diseased foreigner see also Alexandra Stern, Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005); Natalia Molina, Fit to be Citizens?: Public Health and Race in Los Angeles, 1879-1939, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006); Erika Lee, At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration During the Exclusion Era, 1882-1943, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003); and Nayan Shah, Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco’s Chinatown (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001); Alan Kraut, Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the “Immigrant Menace,” (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994).

[i] In the 1920s, the disinfection center added fumigation with Zyklon B pesticide to its list of procedures. On the use of Zyklon B to fumigate Mexican immigrants bodies and clothes see, David Dorado Romo, Ringside Seat to a Revolution: An Underground Cultural History of El Paso and Juárez, 1893-1923, (El Paso: Cinco Puntos Press, 2005), 223, 225. Alexandra Minna Stern, “Buildings, Boundaries, and Blood: Medicalization and Nation-Building on the U.S.-Mexico Border, 1910-1930,” Hispanic American Historical Review, vol. 79, no. 1, (Feb., 1999), 45.

[ii] See Timothy Dunn, The Militarization of the U.S.-Mexico Border, 1978-1992, (Austin: CMAS Books, The University of Texas at Austin, 1996), see chapter two.

[iii] Quoted in Natalia Molina, “The Power of Racial Scripts: What the history of Mexican Immigration to the United States Teaches us about Relational Notions of Race,” Latino Studies, v. 8, issue 2, (2010), 164.

[iv] Quoted in Natalia Molina, Fit to be Citizens?: Public Health and Race in Los Angeles, 1879-1939, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 134.

[v] Natalia Molina, Fit to be Citizens?: Public Health and Race in Los Angeles, 1879-1939, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 123, 134.

[vi] Alexandra Minna Stern, “Buildings, Boundaries, and Blood: Medicalization and Nation-Building on the U.S.-Mexico Border, 1910-1930,” Hispanic American Historical Review, vol. 79, no. 1, (Feb., 1999), 45, 47. For the daily estimate of inspections see page 46.

[vii] Alexandra Minna Stern, “Buildings, Boundaries, and Blood: Medicalization and Nation-Building on the U.S.-Mexico Border, 1910-1930,” Hispanic American Historical Review, vol. 79, no. 1, (Feb., 1999), 42, 72, 68.

[viii] Ana Pegler-Gordon, In Sight of America: Photography and the Development of U.S. Immigration Policy, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 177.