The vans were clean, the road was bumpy and our guide, a U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Agent, had previously worked in marketing for Nike. Before we even got to the San Diego Sector Headquarters, his command staff had been concerned that our art supplies wouldn’t fit inside the vans. Easels and berets? Is that what they were imagining? On the other had, what did we expect? We were a group of artists and other observers on a border mission of our own, guided by the official U.S. Border Patrol. Like the patrol agents, artists and architects observe, demarcate and record landscapes professionally. However, our priorities, methods and traditions diverge widely. Incendiary Traces took this trip in order to view the border from their perspective, and also from our own.

We went to study how the CBP views this site, including the federally mandated and technologically supported methods they use. In tandem, we planned to compare them with approaches that artists and the general public use to survey the border landscape. Incendiary Traces’ goal was (and continues to be) to better understand the urgently political nature of seeing, demarcating, recording and imaging landscapes. This visit served Incendiary Traces’ broader objective of seeking to understand how public and nationally mandated visuality intersect, and how they might influence one another.

Agent Stricklin with map of the San Diego Border Patrol sector | Photo by Jena Lee

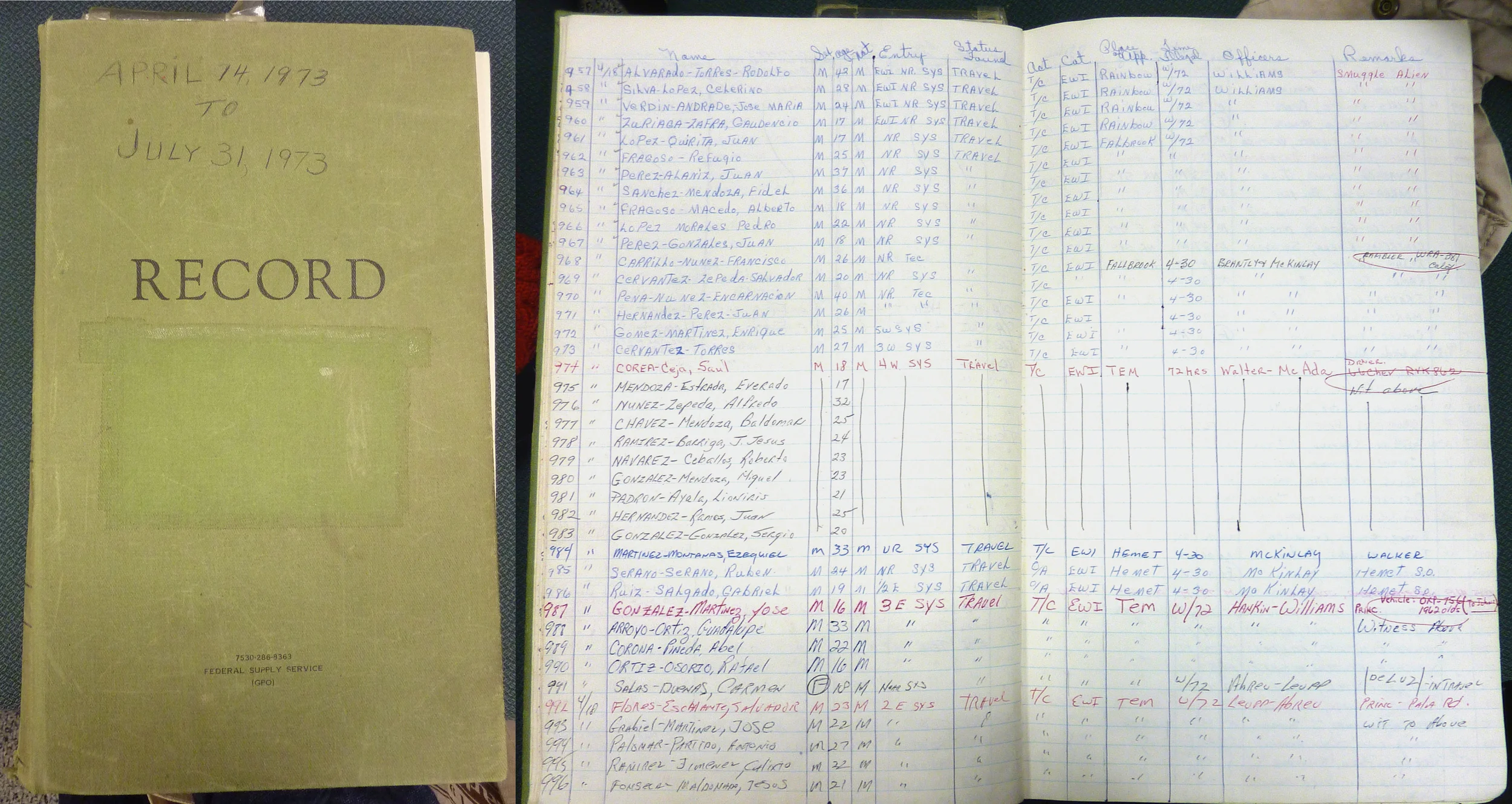

Eva Struble examines a Border Patrol log book from the 1973 | Photo by Jena Lee

A 1973 San Diego sector U.S. Border Patrol log book | Photo by Jena Lee

After Agents Kris Stricklin and Dan Smoak gave a power point presentation at San Diego Sector Headquarters introducing us to a bit of border history and inventive infringement methods of drug cartels, we loaded into two ten-passenger vans and headed to the international border in Otay Mesa. Passing through an alley next to industrial buildings, we entered the space between the border fences through an unmarked gate. We drove for six miles, taking three hours to get to Friendship Circle. We stopped briefly at Colonia Libertad and Smugglers Gulch, and then stayed on Bunker Hill for an hour to draw the landscape as seen from this high point in the Border Field State Park area. A lookout post for well over a half-century, this hill is where the U.S. military dug bunkers into the earth for surreptitiously surveying the border at the Pacific during World War II. As we passed through the fences, the agents described border breaches by many means, and the fallible high and low-tech visual and architectural systems they use to curtail them in the area between Otay Mesa and Imperial Beach.

A view from between the U.S. border walls of a Tijuana neighborhood known as Colonia Libertad, one of the last stops in Mexico for many border crossers | Photo by Jena Lee

Their most obvious deterrent instruments are the parallel border fences. The 10-foot southern wall is built out of military landing strip material surplused from the Gulf War. The massive, dark brown metal starkly contrasts with its surroundings. The northern fence, 15 feet high and made of shiny steel mesh, can be glaring in the Southern California sun. The walls stretch across the county from the ocean to the desert, albeit in fits and starts. Here and there, one of the fences ended against a hillside, another topographical barrier, or simply stopped for unclear reasons, leaving the space between them broadly open. As we drove along the barriers, the distance between them varied considerably. While the walls are typically 150 feet apart from each other, we saw areas where the northern fence veered significantly farther away. For example, one area we passed encompasses an actively farmed field, and in another a third wall appears in parallel, complicating the space even further.

Border crossers often use Sawzalls to cut into the mesh of the border fence as evidenced by the many scars and patches along the northern wall | Photo by Jena Lee

While the fences are hard to miss, they’re also permeable, as the agents explained through numerous examples. First, if one wants to jump the shorter south fence, it just takes a ladder. Getting through the second fence is somewhat more involved. But Sawzalls cut holes, and the surveillance towers can’t detect people directly below them or in the fog, which is frequent by the beach. As we drove on in the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)–only zone between the fences, the agents pointed to a WalMart depot and patches in the steel mesh barrier. The described an instance of smugglers tunneling, climbing and cutting their way from a Mexican church to a drug distribution center hidden next to the depot directly abutting the northern wall.

Surveillance towers are positioned every 200 feet along the border | Photo by Jena Lee

The border fence from above the estuary | Drawing by Amy Adler

In addition to fencing, there are towers with high-resolution cameras and infrared sensors that detect body heat, ground sensors hidden in undisclosed locations, and the infrastructure to support these high tech systems. The cameras are high resolution, with agents in remote offices communicating close-up images of illegal crossers and GPS coordinates to field agents in pursuit. Then there are the agents themselves, 2600 in this sector, covering 8 checkpoints, pursuing illegal crossers by roving in ground and air vehicles. They sit in wait, track footprints on the ground, monitor equipment in remote locations, and apprehend crossers by voice and force.

Here is a border crossing scenario for example. Someone attempts to cross illegally. A spotter (the agents’ word for a person monitoring border patrols from the Mexican side) may help him/her avoid U.S. agents on ground patrol by informing when to make the crossing. If the crosser is seen by an agent—via technological or human sensing—in the process or after making it over the fences, the agents mobilize technological and human forces to find and arrest the person. What are the agents looking for when tracking someone? They could start with footprints. In an effort to conceal their movements, crossers will sometimes use shoe covers made with heavy fabric and wire. In addition, agents are looking for disturbed flora including freshly bent twigs and leaves on the ground. To make tracking easier, agents even comb dirt roads in roving vehicles several times an hour. Maintaining a clean ground surface helps agents see material inconsistencies. Historically, the agency credits Native Americans for developing such tracking techniques, known as “cutting sign.”

Left: Portrait of Agent Dan Smoak; Right: Ant trail on border | Photos by Jacob Janco

The US-Mexico Border looking west from Bunker Hill | Drawing by Eva Struble

Note, there is much debate about the criminalization of the crossers. Political, social, racial and economic issues deeply, sometimes fundamentally, shape people’s perspectives of this place and its inhabitants. However, the position the agents took when asked is that they are simply enforcing the law. Anyone who crosses at a location other than an official CBP checkpoint is breaking the law, even U.S. citizens. While this leveling perspective doesn’t distinguish between drug or human traffickers and other migrants, it points to the fundamentally political nature of perspective at the border. That is, the shape of the border and the lives of its inhabitants are ultimately determined by policy and the ways people and institutions approach it. Thus, viewing and recording this landscape is at its core a political act. As artists, the political nature of our work was strongly underscored here. It put Incendiary Traces participants in a sometimes uncomfortable position of facing the potential power and responsibility of our presence and perspective on this place.

Our driver, a CBP agent, looks out at Smugglers Gulch where a “spotter’s hut” is nestled in the hillside | Photo by Jena Lee

The politics of viewing this landscape became increasingly insistent the more we saw of the CBP route with the agents as our guides. While we were in the canyon east of Bunker Hill, agents apprehended a crosser on the hilltop. When we arrived there to draw 25 minutes later, a pair of homemade booties had been freshly laid on the ground, presumably abandoned during the arrest. Other, older fabric scraps were also scattered around, dirty and flattened from previous scuttles. On average, our guides explained, 78 illegal crossers are caught in this sector every day.

Fabric used as shoe covering by a border crosser in an attempt to avoid leaving footprints that could be tracked by border agents | Photo by Jena Lee

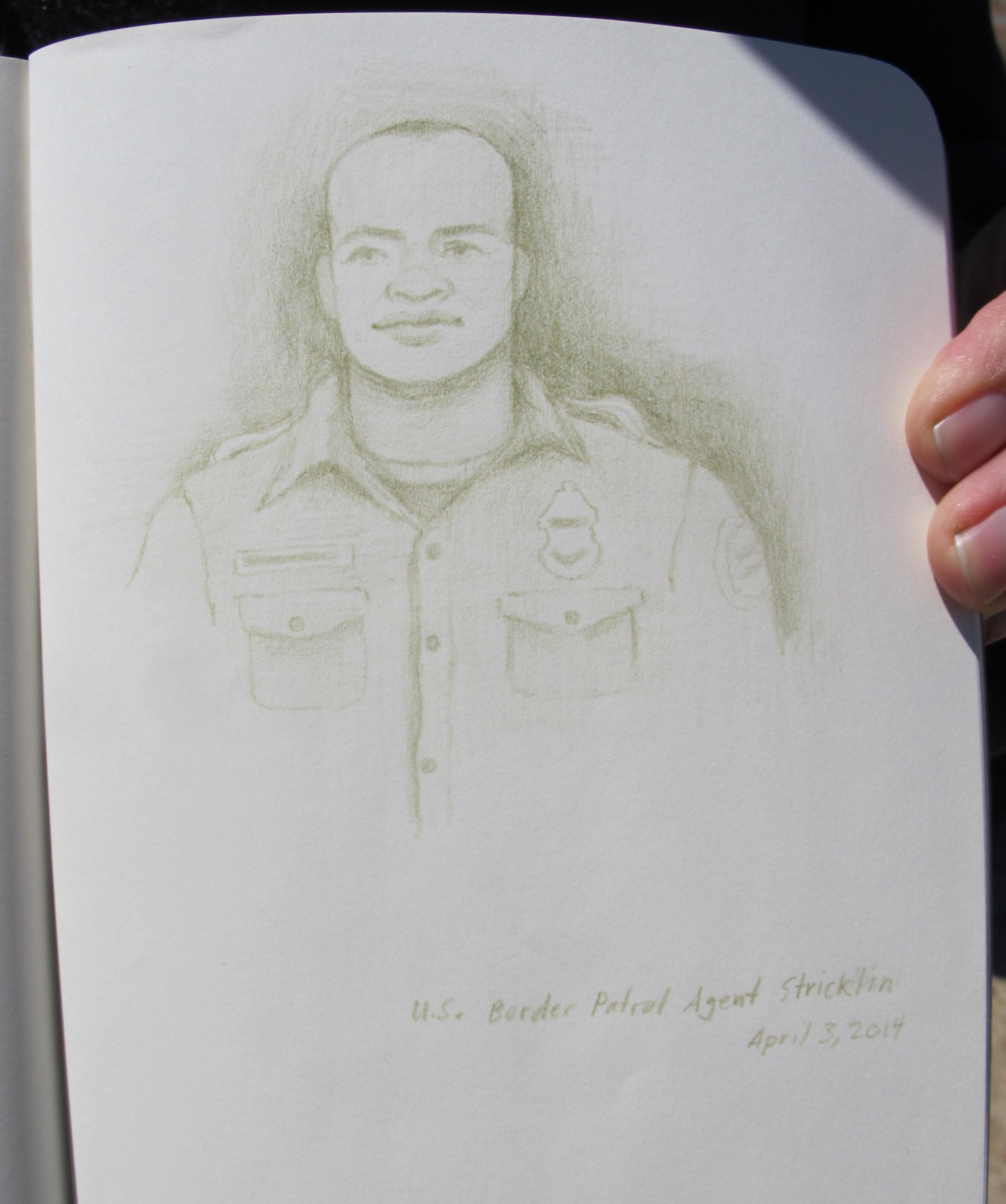

However, our guides maintain that their paramilitary techniques are fallible, and crossers find ways to camouflage themselves. Surveillance towers can’t image people in the fog. Infrared sensors can’t discern people’s body heat if they’re hiding among large rocks, which retain heat. Agent Stricklin described one crosser hiding in the bushes in a ghillie suit, a military camouflage costume of leafy branches and twigs. In this case, the non-native flora was a giveaway to one agent with this knowledge.

Portrait of U.S. Border Patrol Agent Kris Stricklin | Drawing by Amy Adler

Artists, however, are not trained to look for non-native ghillie suits and traces of footprints. But we are trained to observe the environment and circumstances carefully with our own critical criteria guiding us. As cultural producers, we are keen observers of culture and context. In this case, our observation encompassed the landscape and politics of the immediate border and its inhabitants. Our experience gave us a brief sense of immersion in the border patrol culture, including the agent’s perspectives on their work patrolling the area, their perception of imminent or constant threat to national security, and the material and environmental conditions surrounding them. The agents’ perspective of this environment was very different from our own, even as some in our group cross the border daily.

Nichole Speciale observing and drawing atop Bunker Hill | Photo by Jena Lee

The view from Bunker Hill | Drawing by Nichole Speciale

View of the southern border wall | Drawing by Jena Lee

We collected a lot of information by observing the agents perspectives of this environment, and the environment itself. Much of it was complicated; some of it seemed conflicting. To make sense of it requires some synthesis. Incendiary Traces invited Celeste Menchaca to give a brief on-site presentation about historical border surveillance practices to give us further insight. At Friendship Circle, a public park in the DHS-only land between the fences and our last stop with the border agents, Celeste spoke about early 20th century border enforcement history the agents hadn’t covered in their brief slide presentation. In the coastal wind, we clutched flapping copies of a handout she provided with historical images illustrating the story of visual techniques establishing and maintaining the border. The papers included images of surveyors’ instruments, early passport photos, and Mexican laborers fumigated with DDT at checkpoints in the 1950s. There were also photographs of agents in training at the Border Patrol Academy in the 1930s, in classrooms, riding on horses in the desert and looking out across a river while crouching in the brush. Much of this is covered in her essay Crossing the Line: A History of Medical Inspection at the Border, a contribution to the Incendiary Traces archive.

Celeste Menchaca presents a brief history on the patrolling the US – Mexico border at Friendship Circle| Photo by Jena Lee

View from Bunker Hill Looking East | Photo by Brian Ganter

View from Bunker Hill Looking West | Photo by Brian Ganter

Our views of this landscape’s political and physical complexity were barely represented in our image studies created on site that day. However, the process of viewing was uniquely foregrounded in our discussions with the agents, thereby laying out a comparison of perspectives, both visual and conceptual. Many more questions were raised from this experience. For example, what is our role in this landscape? As artists, professional observers, and members of the general public, are we voyeurs, witnesses, tourists, active citizens, interventionists, or something else? The experience ultimately underscored the deeply political nature of viewing, and raised questions about what the public and government agents see, the role of technology, and the connections between authority, observation and perspective.

Incendiary Traces discussed these questions the following day in a public conversation at University of California, San Diego’s Experimental Drawing Studio. The experience and dialog helped establish a new frame for understanding intersections between national security, border issues and artistic inquiry.

Explore a map of our 6 mile route between the border walls | “A Selection of Mapped Utterances, 04.03.2014” (detail) by Elizabeth Chaney - View Elizabeth Chaney's entire map here.

View Elizabeth Chaney's entire map here.