When one visualizes modern war, the images we conjure up might be informed by our engagement with a media landscape dominated by cable television’s 24-hour news cycle. Others might picture soldiers wearing muted desert colored uniforms and the requisite flak jacket and helmet. Still others might call up images from popular warfare video games with near photo realistic graphics like Call of Duty and Counter-Strike, or futuristic cyber warfare titles like Halo and Mass Effect. Without an immediate experience in a war or a close connection to someone who served in the military, most members of the public are left to these mediated images as our guides and the perceptions that this mediation supports. We might assume that the mediated view desensitizes or underserves the public -- that volatile places are potentially rendered distant through a technical lens that abstracts and sanitizes the subject of war. But technological views of war are more complex than that.

Call of Duty: Black Ops 2 | Source: PC Gamer

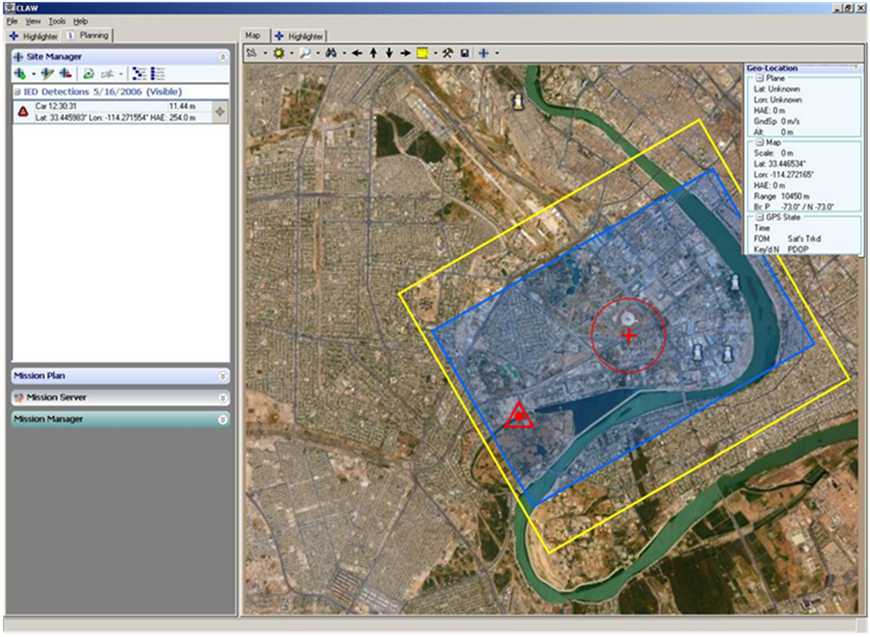

The majority of military personnel are in some way reliant on video feeds and computer screens, and few members have a naked view of their targets. Modern warfare entails the use of data and lots of it. Clusters of surveillance, intelligence, and geographic and other information form their own kinds of maps with their own way of viewing, reading and drawing landscape, targets, and even people. We might think of this as another way of constructing a virtual environment similar to a technology like augmented reality, in which the landscape is layered with levels of information. But engaging in technological warfare this way doesn’t necessarily make it remote. Having more information often means a more prolonged engagement. Having more streams of information might mean we are able to operate with fewer personnel who may be required to work longer to compensate for the lack of bodies. Physiologically, operators may experience heightened levels of awareness and vigilance just like ground operators might [i]. Our reliance on data might actually produce a deeper engagement, not a more disconnected one, thus heightening reality as it were.

CLAW II mission planning software is used by unmanned aircraft operators identify and locate targets | Photo: General Atomics

Despite rapid technological advances, humans still retain a mind that responds to stimuli on an unconscious level. The technological stimuli found in both video games and computer programs used for military training easily stimulate functions that once aided our evolutionary adaptation. When contemporary interactive technologies engage more than our fingers and eyes, they also activate our higher level functioning. Technologies typically used to create entertainment media also work remarkably well as a tools for training and learning. Simulations in computer games and virtual reality are radically altering the way the military prepares soldiers for war.

Soldiers use the Mobile Counter Interactive Trainer | Photo: USC Institute for Creative Technologies

For the military, simulation offers realism with mitigated risk to personnel. It also bridges classroom learning with practical opportunities for rehearsal and evaluation in portable, endlessly repeatable formats. Critics might argue that seeing in a digital environment is somehow less real than what we see in everyday life, therefore providing trainees with misrepresentations of the battlefield. However, the idea that seeing in the real world is somehow objective, while seeing in the virtual world is not objective, sets up a false dichotomy. The act of seeing is much more subjective than we would believe and none of us sees the world in the same way. Seeing only begins with our eyes. What we perceive -- a more accurate term -- is also subject to environmental and emotional conditions. It is this subjectivity that allows programmers to account for and guide our perceptions in virtual environments. Think of an optical illusion in which what we think we are seeing is not necessarily so and you’ll have a glimmer of how perception works. In vertebrates the act of seeing occurs when light enters our eyes. This light is turned into a signal that the brain can interpret. There is a process that occurs in the brain before the signal is turned into a conscious thought in which we identify what it is we’re looking at. We are always evaluating the information before us. Though we live in a world of 10+ megapixel resolution digital cameras, each eye only has about 4.5 million cone cells (able to perceive 4.5 megapixels) and 90 million rod cells (90 megapixels). A megapixel is 1 million pixels [ii]. Most of the cones, the cells responsible for detecting light and color, are located in the center of the eye, while rods, the more sensitive but non-color detecting parts are located around the whole eye. This gives the center area of the picture good resolution, while the peripheral vision has much less visual acuity [iii]. What we think we see is so crisp and clear thanks to the way our brain extrapolates based on expectation and experience.

U.S. Army Soldiers conduct virtual dismounted training using a military alternative to the Virituix Omni and Oculus Rift | Screenshot from ArmyVideoTube

In simulated environments, authenticity, belief and comprehension of the virtual landscape come from immersion within it, which in turn depends on effective methods of navigation. Comprehension of virtual landscapes requires users to travel between coarse and fine levels of information, which they use to orient themselves and establish a sense of being in a place [iv]. A variety of cues can provide information on location, orientation, rate of movement and field of view [v]. We use similar visual cues to understand and navigate our own environments when we perceive that the street is at a certain distance and the mountains are also at a certain distance. Credible views of landscape are often achieved by means of "white lies," like conventional 2-D maps where shading and shadowing is used to exaggerate a particular direction to help users navigate the space effectively [vi]. These discrepancies in the representations of virtual landscapes are designed to work with the way we see and navigate the real world around us. When virtual reality is added, such as the use of head mounted displays (HMDs), users not only see digitally rendered environments, they perceive that they are physically occupying those environments. An HMD adds the sense of presence or the feeling that one is actually in the environment or has spent time in a place that feels wholly real and familiar. With such environments we move from seeing to a grounded experience. While there’s no fixed definition for presence in virtual environs, theories are beginning to be formulated. Behavioral and social science researchers for the U.S. Army Research Institute, Bob Witmer and Michael Singer propose that, “presence is defined as the subjective experience of being in one place or environment, even when one is physically situated in another [vii]. Returning to our earlier example of the ways computer games engage our brains, U.K. University College London Professor of Virtual Environments, Mel Slater states that, “when you are present your perceptual, vestibular, proprioceptive, and autonomic nervous systems are activated in a way similar to that of real life in similar situations. Even though cognitively you know that you are not in the real life situation, you will tend to behave as if you were, and have similar thoughts (even though you may dismiss those thoughts as fantasy) [viii].” A sense of presence in the virtual environment creates a relay between the place and the representation of the place.

Virtual environments have given rise to an interesting and unclear relationship between the dialectics of space, place and the form and content of representation [ix]. While geographic distance to war zones is a physical reality, new technology leaps over distance and brings to us unprecedented levels of detail. Data rich representations of conflict zones may offer us a clearer picture and even a prolonged look at conflict zones that are thousands of miles away. Rapidly evolving virtual reality and related technologies may let us impact those environments in real time through our virtual presences. While mediated and virtual representations of war are already common, the ways we understand our proximity to war and presence within war zones will become increasingly complex.

Notes:

[i] Chow, Denise. "Drone Wars: Pilots Reveal Debilitating Stress Beyond Virtual Battlefield." LiveScience. TechMedia Network, 05 Nov. 2013. Web. 7 July 2014. http://www.livescience.com/40959-military-drone-war-psychology.html.

[ii] "The Resolution of the Eye." The Resolution of the Eye. N.p., n.d. Web. 7 July 2014. http://www.eye-therapy.com/Resolution/.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Unwin, David. "Virtual Landscapes." Virtual Reality in Geography (Geographic Information Systems Workshop). By Peter Fisher. London and New York: CRC, 2003. 96. Print.

[v] Ibid., 96.

[vi] Ibid., 96.

[vii] O'Neill, Shaleph. "Presence, Place and the Virtual Spectacle." PsychNology3.3 (2005): 149-61. Web. 7 July 2014. http://www.psychnology.org/index.php?page=psychnology-journal-volume-1-number-3.

[viii] Ibid., 149-161.

[ix] Ibid., 149-161.