“Somewhere in the California Desert, under a molten sun and in a country where the very earth feels like fire, American armored vehicles are training….It is this force that will someday leave death in its wake in the sandy places of Libya, or wherever it may be sent.” i

Thirty miles east of Indio, California in a largely uninhabited desert landscape, sits the largest military training ground in United States history, though you might not have heard of it. During its two years of operation over a million troops trained in its desert heat, in an area roughly 18,000 square miles, a district larger than the states of Maryland and Delaware combined. Created in the spring of 1942, the Desert Training Center stood in for foreign landscapes that American troops would soon face, particularly those in North Africa.

While few structures of the Desert Training Center remain, various organizations have memorialized its location. This plaque rests at the General Patton Memorial Museum in Chiriaco Summit, California. Photograph by Scott Seekatz.

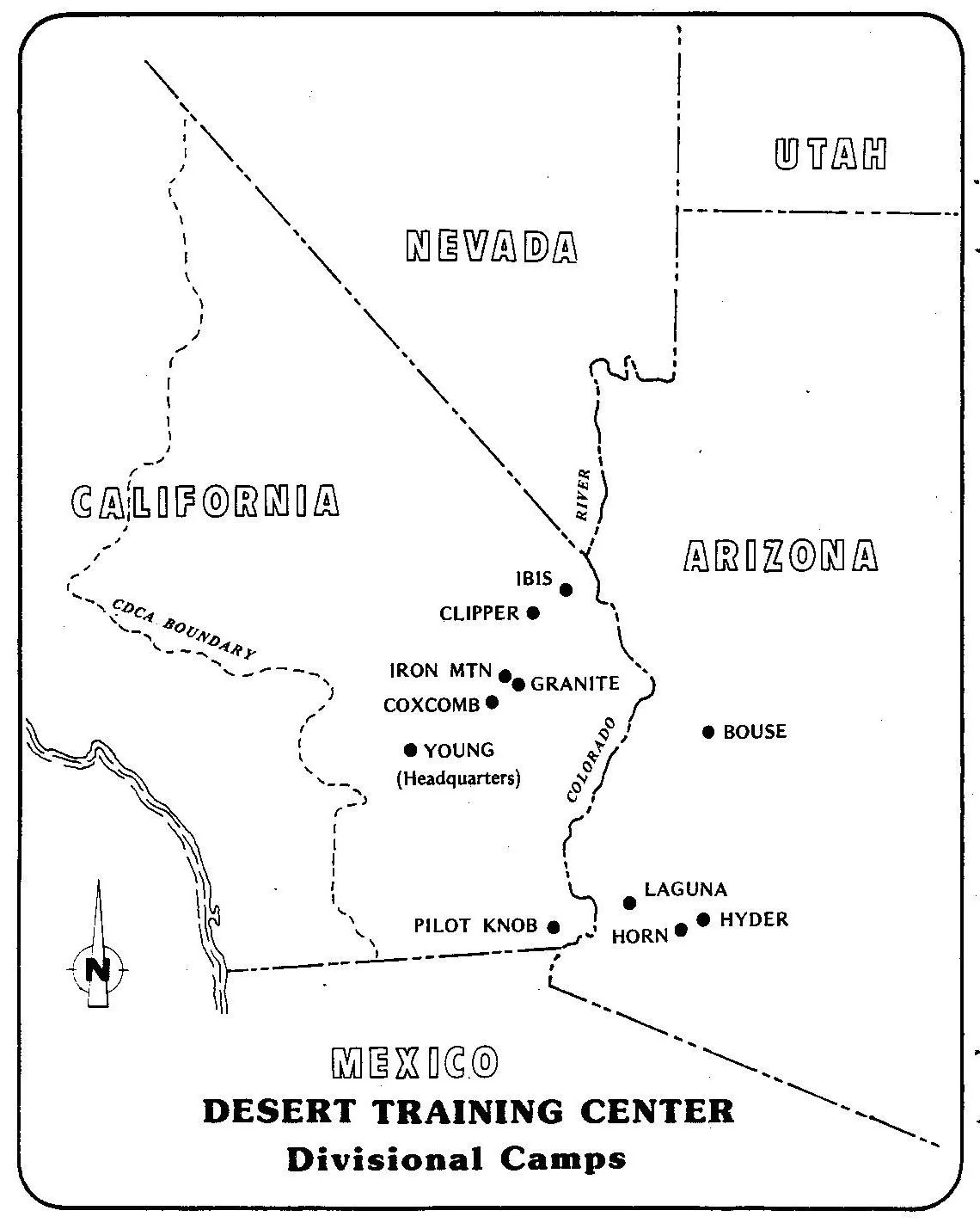

The Desert Training Center/ California- Arizona Maneuver spanned three states, though the majority of divisional camps and the headquarters were located in California. Area maps courtesy of the Bureau of Land Management, Needles Field Office.

Fighting in North Africa began in 1940 as European powers that held colonial interest there battled to maintain control of the region. At stake was crucial access to oil and, for the British, access to their broader empire in Asia and Africa via the ever important Suez Canal. Germany’s Afrika Korps demonstrated success in desert warfare in the region, encouraging the United States to focus on North Africa as they entered the fight. While it is often overlooked in U.S. History courses, the Allied victory in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia served as a proving ground for U.S. troops and leadership before crucial battles in Europe and the Pacific.

General George Patton Jr. not only picked the location of the Desert Training Center but his goals and objectives had a lasting effect on the center, though he was only there for five months. Here Patton (touching table on the left) and other officers are initiated into the Veterans of Foreign Wars at the Desert Training Center. Courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum.

Yet at the outbreak of war, American troops sat woefully unprepared for battle, indeed even for surviving the harsh desert climates of North Africa. The army pushed for training in desert warfare and placed General George Patton Jr., a Southern California native, in charge of selecting a site and creating what would become the Desert Training Center (DTC). “I want my men to take just a rough a beating as I can give them in as near the situation they will have in North Africa,” Patton intoned. ii

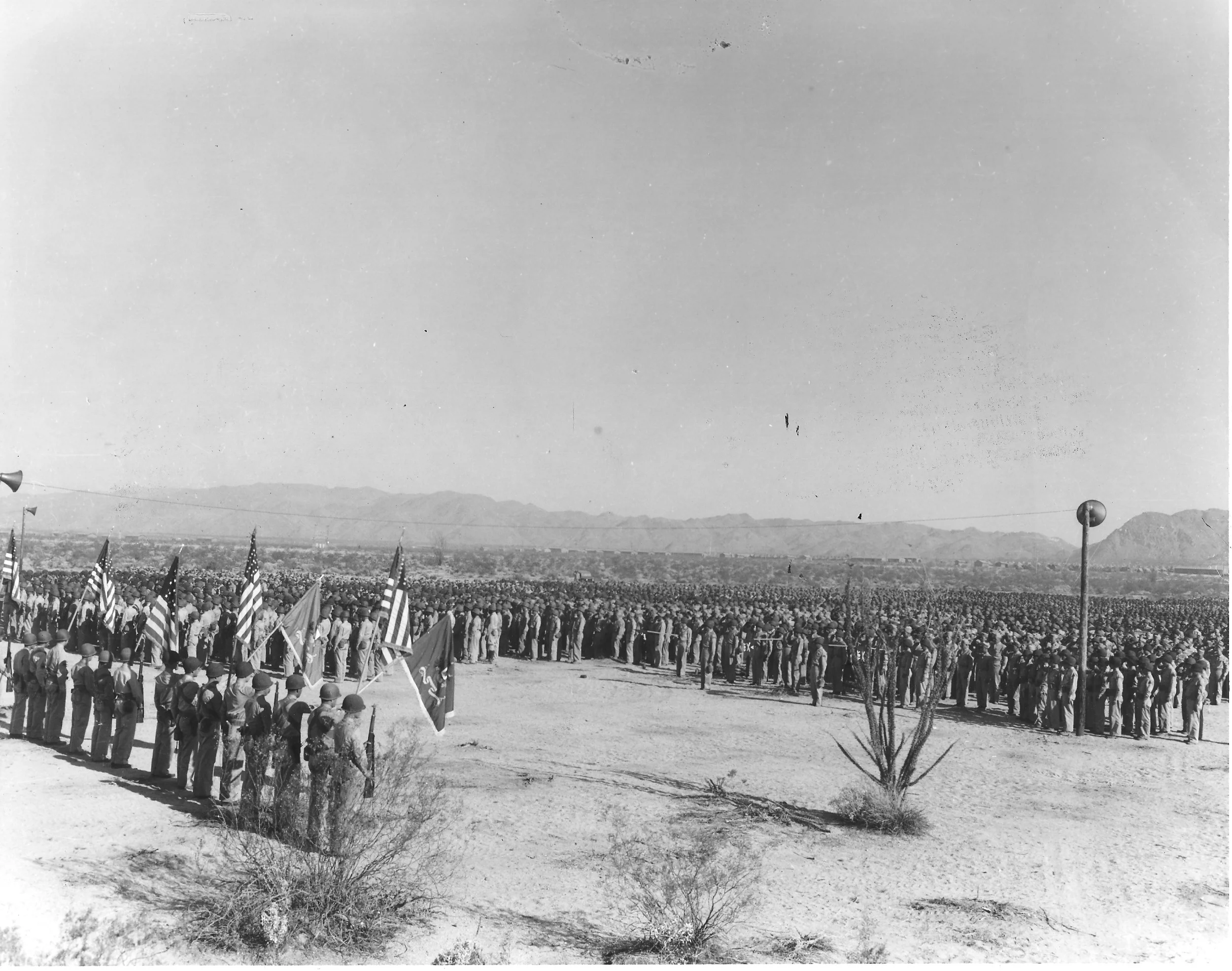

Here soldiers, and likely local press and dignitaries, listen to an address by Patton at the Desert Training Center. Patton’s larger than life personality and premature death contributed to both locals and troops’ emphasis on the general in DTC memorial attempts. Courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum.

For American troops, fighting in North Africa lasted a short while (a little more than 6 months), therefore focus on desert survival and warfare became secondary to general military training for deployment to the European and Pacific Theaters. As a result, the army renamed the Desert Training Center the California-Arizona Maneuver Area (CAMA) in October 1943 to reflect its non-desert capacities. It served as a simulated “Theater of Operations” until spring 1944.

The desire to create a training center in the desert left much of the Southwest as a prime target. The decision to go with the portions of California, Nevada, and Arizona ultimately selected rested on multiple factors. First, the land lay largely under the jurisdiction of the federal government. Just as important, however, was the region’s access to water, as the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California’s Colorado River Aqueduct flowed through the region and provided water for the DTC. The center rested nearby transportation systems that would not only bring men but supplies as well, particularly the Southern Pacific Railroad which ran from Los Angele to Yuma, nearby many of the training camps. While communication and electrical lines required additional work from both the army and local utility companies, the close proximity of the Coachella Valley meant these systems could be established relatively quickly as well.

Soldiers disembark at the Freda railroad siding, off what is now Highway 62. Established railroad lines made the Desert Training Center ideal for transporting troops and equipment. U.S. Army photograph, courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum.

Importantly, the area functioned as a desert in both senses of the word, an arid landscape that supported sparse vegetation and a place mostly devoid (or deserted) of people. When General Patton first surveyed the area he failed to encounter a single inhabitant in his four day reconnaissance. The lack of civilian presence proved a boon for army training. Maneuvers with live ammunition could be conducted without fear of endangering the public and testing of equipment and tactics remained relatively secret. The vast expanse of land allowed for large scale exercises that helped both officers and enlisted men develop and practice tactics used in actual warfare. Conditions mimicked landscapes the men would come to inhabit in North Africa. One army official remarked that “The terrain at the Desert Training Center is far worse than anything in Libya or Mesopotamia. American troops at the center are more competent to go into battle today than any unit with which I have served.” iii

Soldiers practice with field artillery near Needles, California in September 1942. U.S. Army photograph, courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum.

As the Incendiary Traces project suggests, the landscapes of Southern California often serve as stand-ins for foreign spaces, formilitary preparation in particular. By World War II, the entire Southwest, especially the nearby Coachella Valley, had long been America’s substitute for North Africa and the Middle East, and thus a logical starting point for desert warfare training. Early American settlers to the region contextualized the strange landscapes with comparisons to biblical lands. After its accidental formation the Salton Sea was frequently described as America’s Dead Sea, while nearby cities shared names with other places in the Greater Middle East: Mecca, Arabia, Edom. The region’s unique success with a Middle Eastern and North African crop, the date, continued the ties by brining foreign flora and more than a hint of romance to the area, a link continued even today at the “Arabian” themed Riverside County Fair and National Date Festival.

This image, by Captain Ray “Swede” Fernstrom, is identified as a typical desert base in North Africa. Information indicates the photo on the right was also taken in North Africa. Note the striking landscape similarities to the photograph of the Desert Training Center below. Courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum.

View near Chiriaco Summit, California, then known as Shaver Summit, once part of the Desert Training Center. Screen shot of maps.google.com.

When Hollywood set out to make movies with the romance of the so called Orient, they too turned to the region as a double for North Africa and the Middle East. Films like Salome (1918), The Shiek (1921), The Son of Sheik (1926), The Veils of Bagdad (1953), and Omar Khayyam (1957) were filmed in the Southern California desert. In fact, during and after World War II, Hollywood used the area as filming location for movies about North African desert warfare. The Five Graves of Cairo (1943), for example, not only shot in the region but also at Camp Young in the Desert Training Center, working with the army to stage battle scenes near Yuma. Sahara (1943), too, boosted ties to the DTC, with some DTC soldiers playing German soldiers in the Academy Award nominated film.

Filmed in and near the Desert Training Center, Sahara not only featured Humphrey Bogart (kneeling at left) but also members of the Fourth Armored Division who trained at the DTC. Courtesy of Eve's Magazine and Kenneth Koyen

Long established as the American version of “Arabia,” the local landscapes promised a quick solution for desert training as the nation strove to prepare its soldiers for battle in North Africa. The region’s climate and landscape remained the closest American troops could get to the realities of their future battlegrounds without leaving the nation. The heat, in particular, was important. Patton argued “We cannot train troops to fight in the desert of North Africa by training in the swamps of Georgia.”iv Knowing the danger associated with the desert, he went on: “The California desert can kill quicker than the enemy. We will lose a lot of men from the heat, but training will save hundreds of lives when we get into combat."v Indeed, during maneuvers away from camp, men lost their lives in the heat, with locals in Yuma and Phoenix registering protests over the training conditions.vi

Members of the 68th Tank Battalion of the 6th Armored Division stop for a drink in 1943. Leadership believed (erroneously) that rationing could condition bodies to use less water, especially if battle limited water supplies. Men often had one gallon per day for all their needs, including drinking and bathing. Photography by Olan Hafley, courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum.

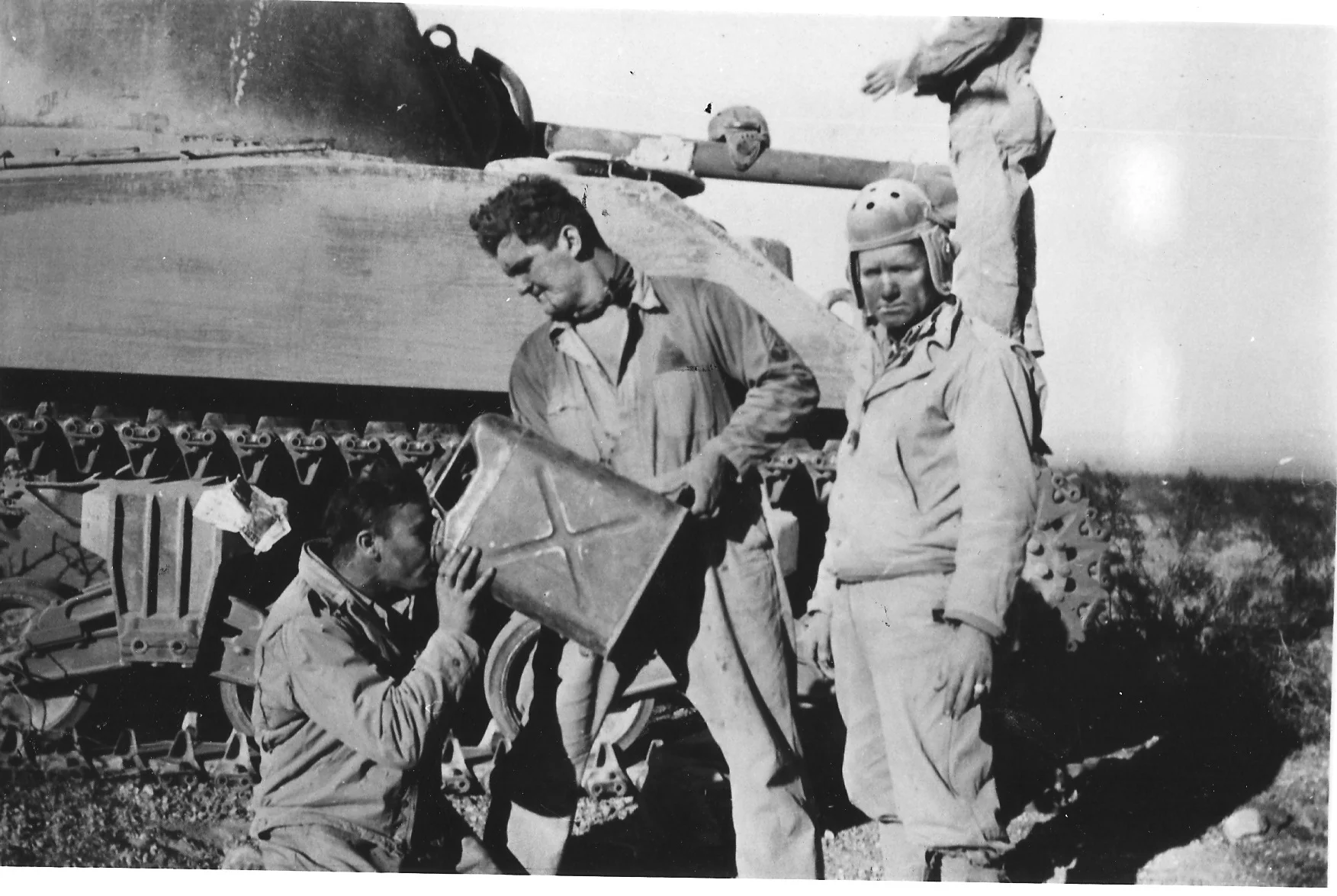

Few of the troops had ever experienced the dry climate and they struggled to acclimate to temperatures upwards of 120 degrees and brutal sandstorms. Salt tablets were distributed to the men, in hopes they would prevent dehydration and cramping, but water was rationed. Sometimes, particularly early on or while out on maneuvers, troops received only one canteen of water per day, with an erroneous understanding that one could be trained to survive on less water and that such deprivation prepared them for the harsh conditions they would face in North Africa. Men learned to keep cool without much shade and to avoid the natural dangers of the desert like rattlesnakes and scorpions. The testing of equipment proved equally important and led to practice in desert camouflage, better maintenance of tanks and other vehicles, and even new supplies like dust respirators.

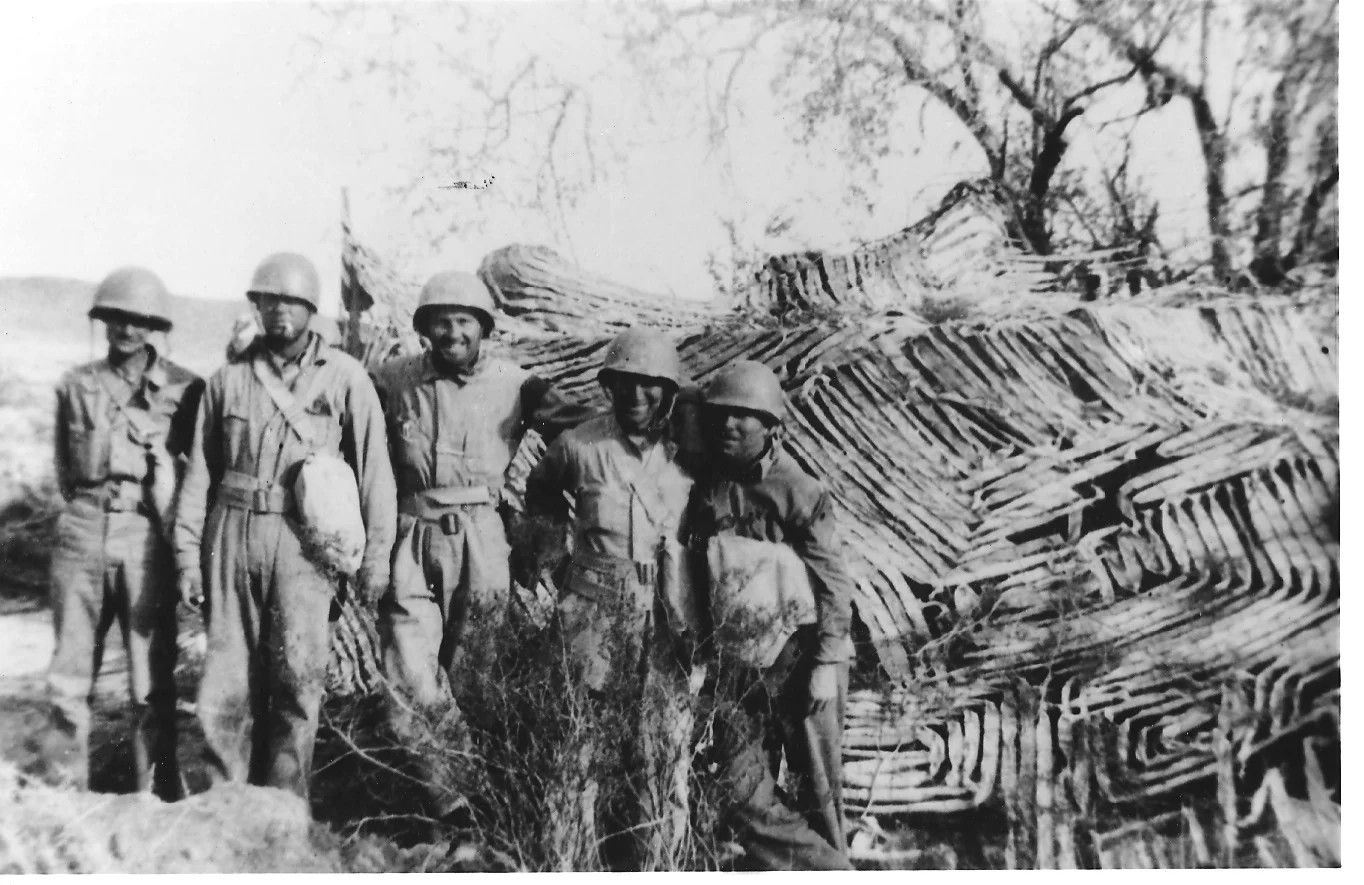

Soldiers pose near a camouflaged tank at the Desert Training Center. Training allowed the army to better understand desert conditions and how to camouflage their equipment and men in sandy landscapes with sparse vegetation. Courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum.

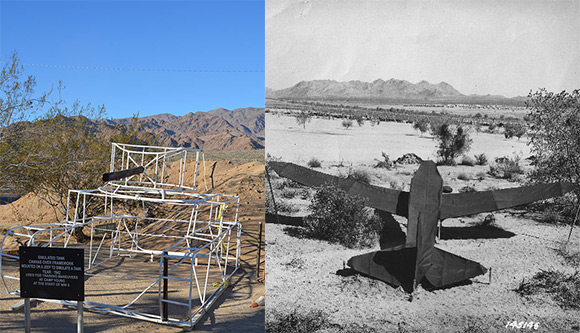

Though troops at the DTC often practiced with real tanks, simulated tanks like these were occasionally used during training. This skeleton would be mounted on a jeep and covered with fabric to reproduce the tank effect during maneuvers. Today the General Patton Memorial Museum houses this reproduction. Photograph by Scott Seekatz.

To prepare bodies for long hours and hard work, all troops were required to run a 10 minute mile with gear within a month of their arrival, an activity that not only acclimated them to the desert but also hardened their bodies and minds for the challenges that lay ahead. This “seasoning” of the men proved an important goal; while abroad troops sometimes faced desolate locations, cut off from supplies or even water, lacking shade and the comforts of home. Even as the Desert Training Center shifted to broader training operations after fighting in North Africa ended, officers celebrated the hardening of men as crucial preparation for the difficult conditions faced in Europe and the Pacific. That the landscape varied, with valleys, rocky foothills, and mountain ranges, served as an additional bonus; troops could prepare for diverse battle terrains.

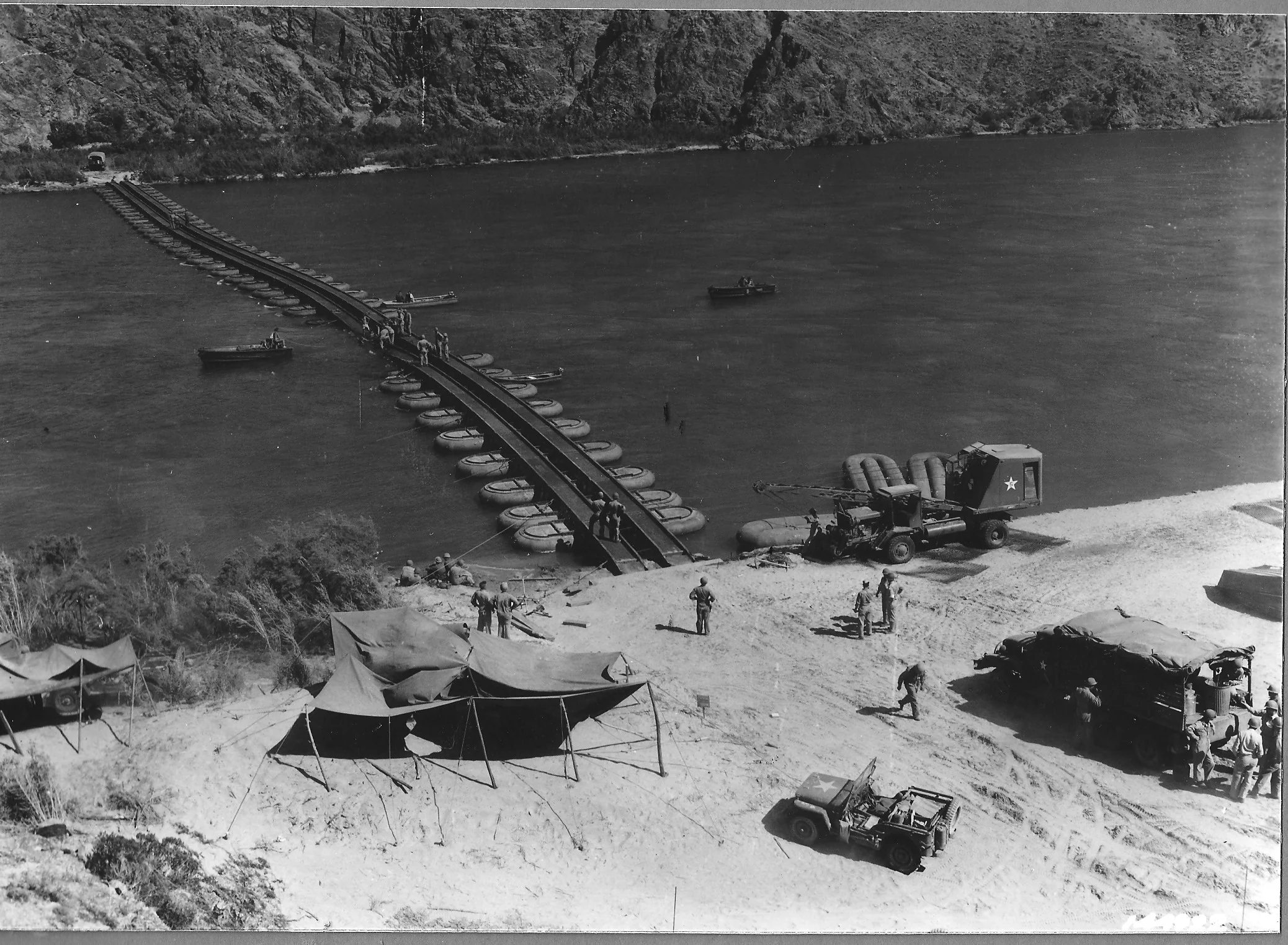

The varied terrain of training grounds allowed for troops to practice their specialty in landscapes similar to those encountered abroad. Here army engineers practice constructing pontoon bridges across the Colorado River. Courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum.

The vast expanse of land provided enough room for multiple battalions to train in situ, to create living spaces from the ground up, and experience maneuvers that mimicked actual warfare. Engineers outlined camp roads, signal corpsmen laid telephone lines, and army air corpsmen took advantage of year round clear skies to obtain crucial flying skills and practice. Thus troops gained actual practice in the roles they would hold abroad in a landscape and climate similar to what they would encounter. They did so in their units which bonded the men together, particularly because of the isolation and new experiences they shared. Difficult conditions provided confidence to men who worked through them; even the days without sleep and hundred mile marches provided a taste of what was to come. Patton’s early emphasis was on constant movement; not only did this train the men for actual combat situations but made it more difficult for the enemy to find and destroy a camp as well. Thus while the Desert Training Center held about 14 divisional camps, much of the training happened beyond their borders in the raw desert landscape.

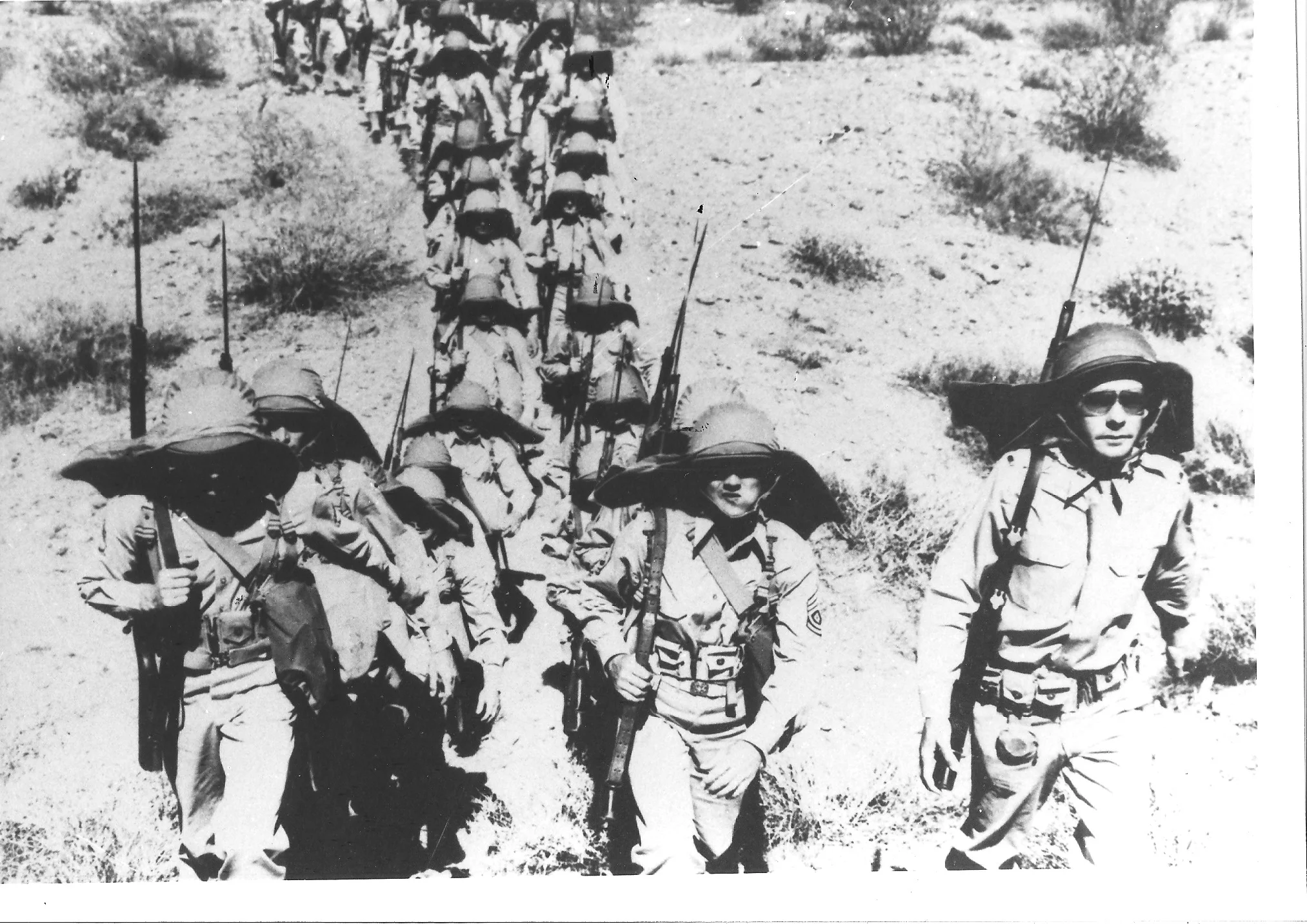

Troops march through the landscapes of the Desert Training Center. Photo by Bill Threatt, courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum

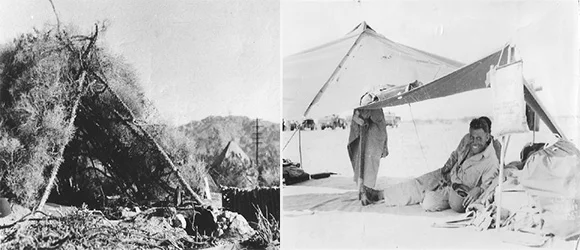

While the divisional camps held larger canvas tents that slept multiple men and had some of the comforts of home (though no electricity or running water), troops spent much of their time in the field and thus in makeshift dwellings. To the left is a “maneuver home” constructed of ocotillo branches and brush. To the right, a soldier rests under a rudimentary tent. Note the bag of water hanging from the right side of the structure; it likely had to serve all of his drinking and bathing needs for the day. Some recalled using gasoline to try to prevent scorpions and snakes from crossing into their tents, but gas was scarce, especially while in the field. Courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum.

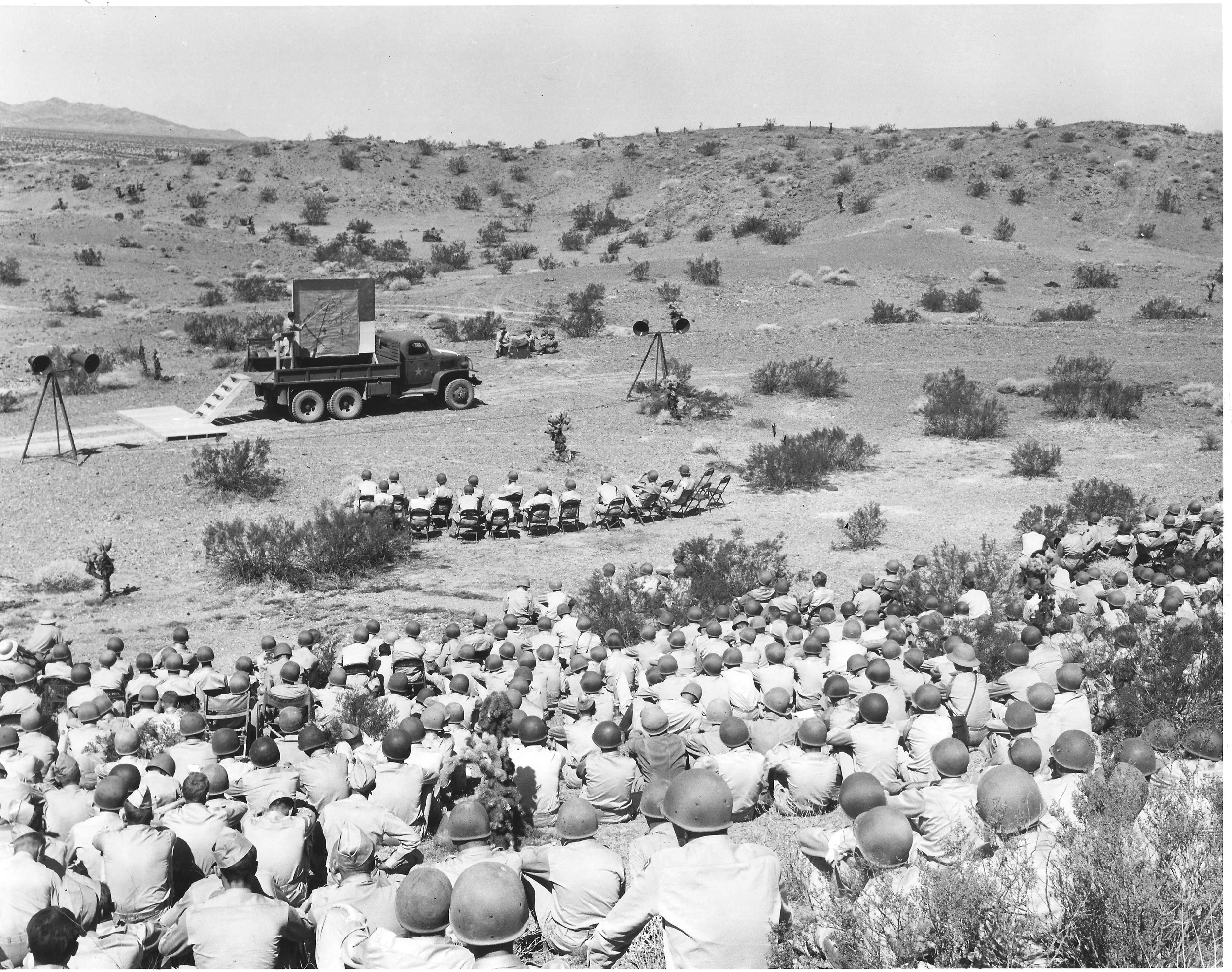

By the time soldiers reached the Desert Training Center they had already completed basic training and training in their specialized fields. Their 13 or more weeks in the desert allowed them to receive additional practice in their area of expertise at or around their base camp; work together as a unit on the move, constructing temporary shelter and learning survival skills; and importantly, participate in large scale maneuvers that brought in nearly all units at the center, upwards of 10,000. These large scale maneuvers mimicked battles, with leadership watching from afar, reviewing performance, and discussing successes and weaknesses with troops directly afterward. These 1-2 week maneuvers mimicked battles in North Africa, particularly when troops traveled 100 miles to engage in what some referred to as “war games” with teams battling each other, purportedly with live ammunition. The military was in direct contact with Allies and eventually their own men in North Africa, which meant training at the DTC could reflect the latest understanding of battle conditions. After massive American losses at the Battle of the Kasserine Pass, for example, maneuvers moved to the Desert Training Center’s Palen Pass area which mirrored Kasserine’s landscape. Only in such an expansive, relatively unpopulated area could varied units, from communication specialists to aircraft pilots and tank battalions, practice together.

Officers listen to reviews of a maneuver held five miles from Needles, California at the Desert Training Center in September 1942. U.S. Army photograph, courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum.

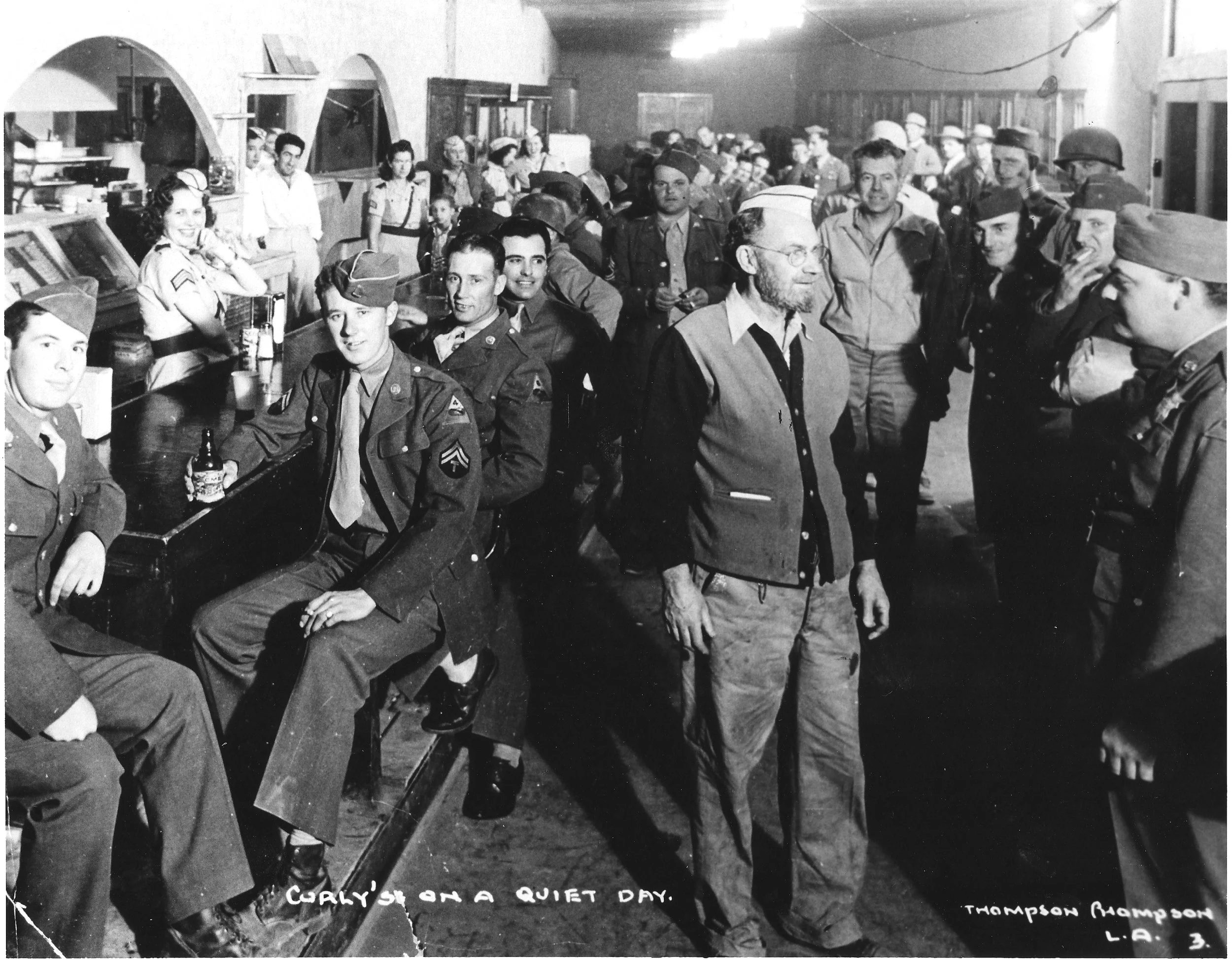

While the remoteness provided a realism found in few other military training grounds, it also led to a sense of isolation and boredom among the men, sometimes resulting in low morale. Troops were allowed to venture out in their off time (normally 3 days per month), drastically impacting the surrounding communities. Yuma, then home to 5,000, was overrun with 3,000 soldiers in a single Saturday night, upsetting local residents who received no assistance from military police. Because of its proximity to the DTC headquarters in Camp Young, Indio bore the brunt of the soldier influx which ultimately proved a boon to the local economy. While some resented the flood of men, many local clubs and churches opened their facilities to the servicemen. USOs were organized in Indio and Coachella providing refreshments, showers, a photographic darkroom, and even a swimming pool for the troops. While the communities around the DTC had the comforts of home, their desert setting and even their North African themed date shop architecture likely reminded the men of their ultimate destination once their training completed. For many of these men, training at the DTC/ CAMA served as an introduction not only to the desert, but to California. They would return years later to show their families where they trained, sometimes moving to communities nearby.

Curley’s Bar in Rice, California full of soldiers from the Desert Training Center. An influx of soldiers drastically impacted local communities; while business increased, price gouging affected troops and locals alike. Thompson photograph, courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum.

Tanks are unloaded at the Indio rail yards in December 1942. The army’s use of the railroad disrupted both passenger and cargo transport; local rail yards experienced labor shortages throughout the war as keeping up with army supplies, equipment, and men seemed a never ending challenge. U.S. Army photography, courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum.

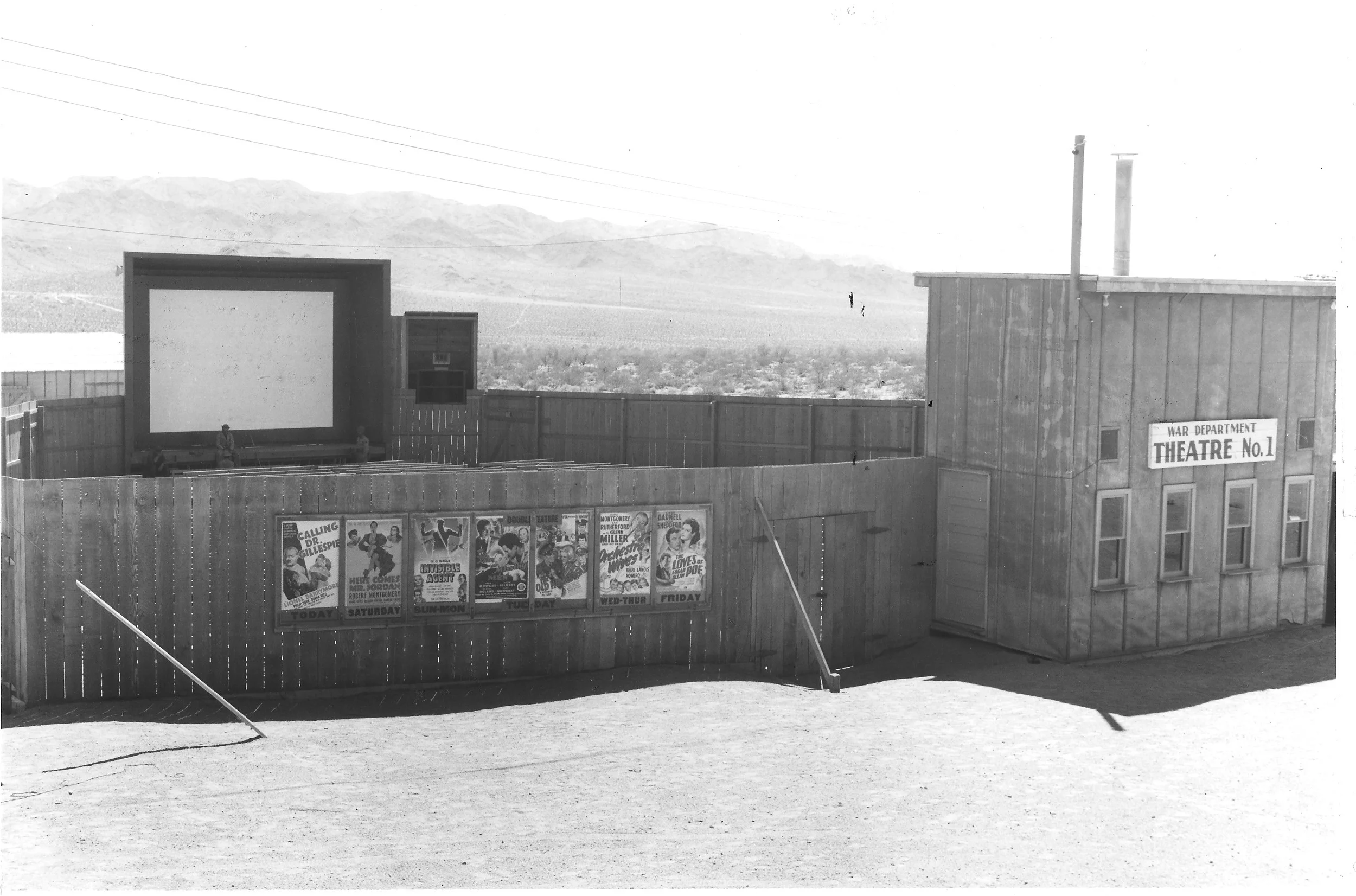

A theater operated inside the Desert Training Center, though many troops saw films in the nearby communities while on leave. Other entertainment options included baseball leagues, USO shows, and dances though much of soldiers’ free time was spent in the field, playing cards or writing home. U.S. Army photograph, courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum.

The USO sent entertainers like Bob Hope and organized nighttime baseball leagues at the DTC. Saturday night dances were particularly popular. While Patton initially refused to allow women to work on the base (as needed telephone operators during the early days of Camp Young), they were welcomed during the dances. “Shortages” of women were apparent in dances thrown both in Indio and on base. To rectify the problem Hollywood elite organized the Desert Battalion, a group of 18 to 25 year old women from Los Angeles who paid their own way to the camps in order to provide chaperoned company and dancing partners for the troops. Similar groups brought additional women to the region, including African Americans who hosted dances at segregated USO facilities. These volunteers later recalled their feelings of duty to talk and dance with the men who were often away from home for the first time, missing sisters, girlfriends, and mothers. The wives of some servicemen, particularly officers, made their way to the nearby desert, shifting the surrounding communities. These women often filled in as cashiers, waitresses, shopkeepers, and even in date (fruit)-packing as locals moved towards metropolitan areas for defense work. Some Coachella Valley women protested their treatment by the young, single servicemen who inundated the town; the Indio Women’s Club met with Patton who dismissed their objections by saying “If I were you women, I wouldn’t worry if they whistled at me. If I went into the street and they didn’t whistle at me, then I’d worry.” vii

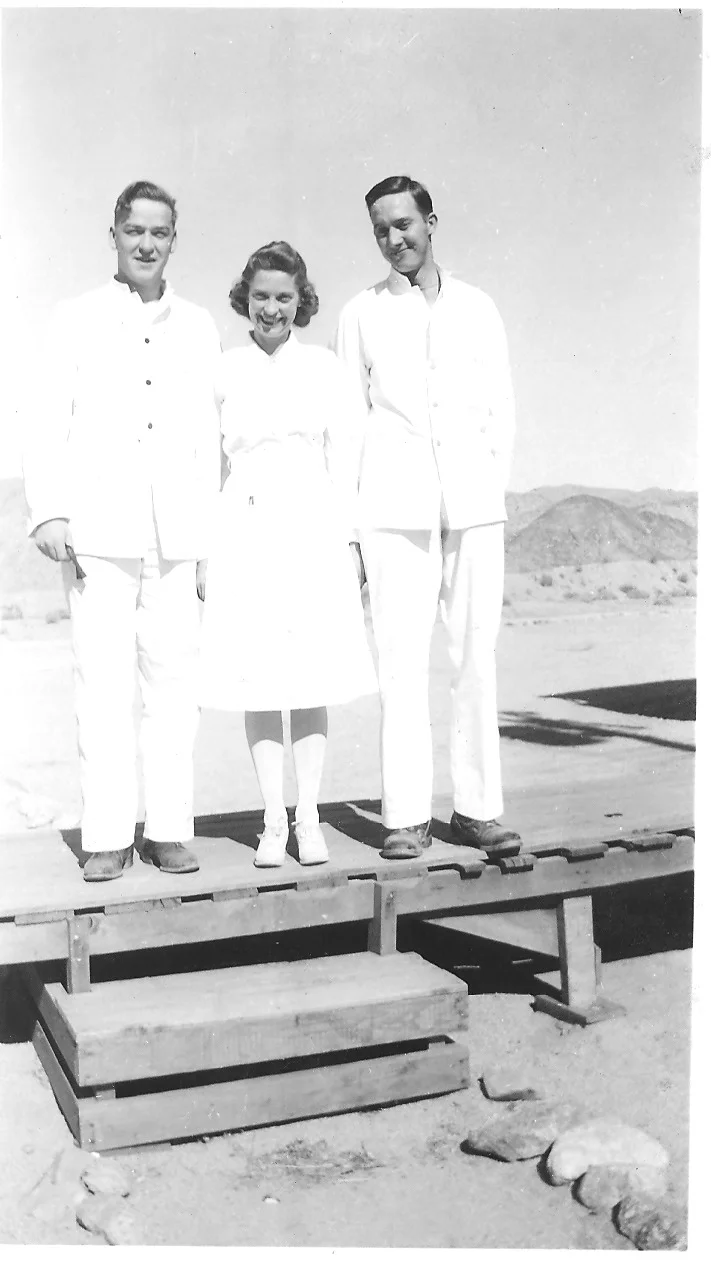

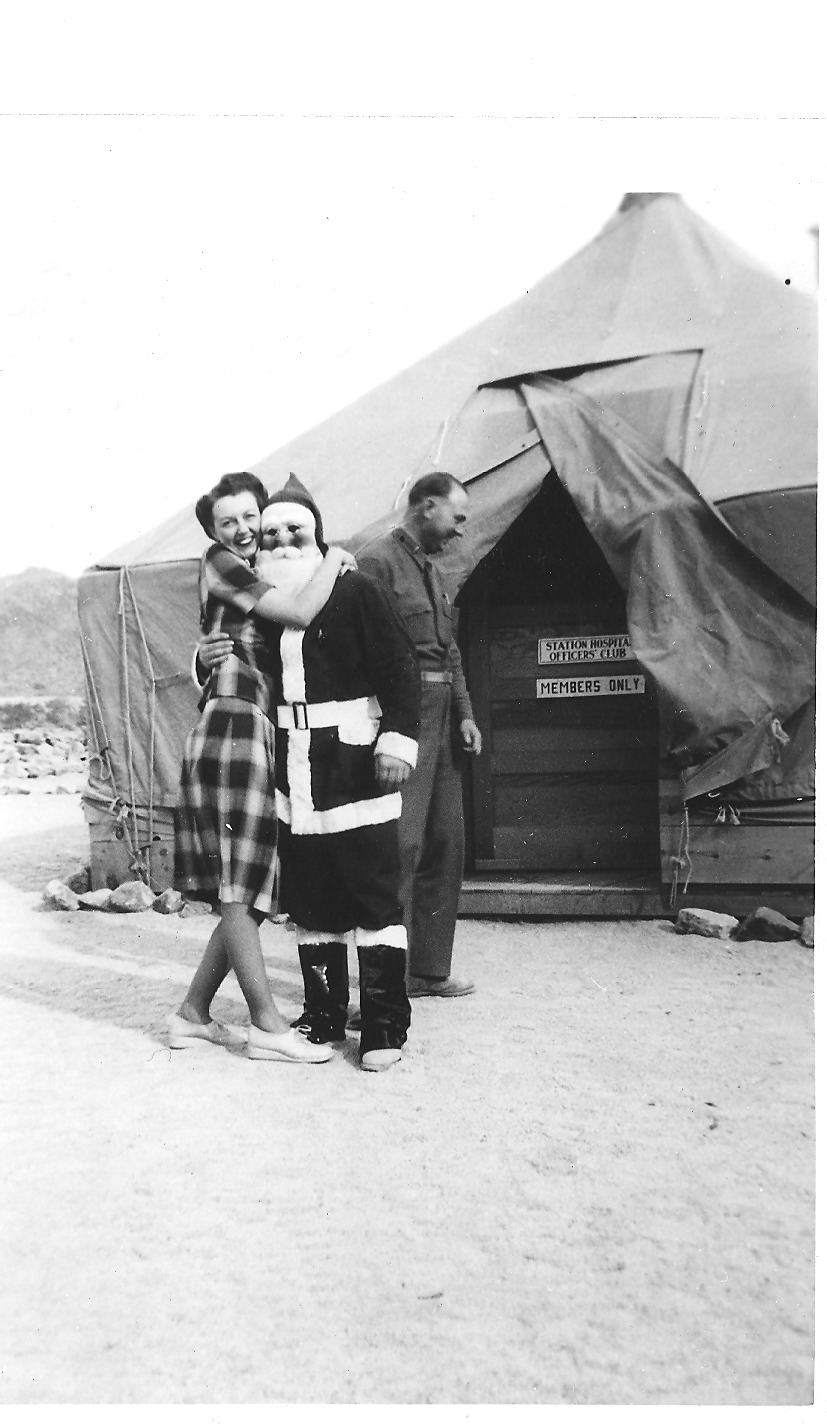

Patton initially refused women at the DTC, preferring that soldiers focus solely on training. Eventually, women worked as nurses and secretaries, especially at the DTC’s Camp Young Headquarters. Here a nurse from the Camp Young Station Hospital poses on the left. To the right a woman hugs Santa outside of the Station Hospital’s Officer’s Club. Courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum.

The Desert Battalion and other groups like it bussed in young women to serve as dance partners and conversationalists for the soldiers stationed at the DTC. Courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum.

Not all soldiers were offered the same entertainment opportunities. Black soldiers faced segregation when they entered the town of Indio. While nearby white USOs offered hot showers, a musical library, and plush accommodations, black soldiers waited some time for a USO which only appeared due to the aid of the black community of Indio. Even the army reported this location as “the inadequate Negro U.S.O. whose development and improvement was delayed until practically the close of the” DTCviii. Moreover black soldiers could only eat at a few segregated restaurants in Indio. Lack of facilities, restaurants, and entertainment venues for black soldiers occasionally resulted in scuffles and threatened violence. That the military police who oversaw these black troops were almost exclusively white was cited as a cause of at least one “riot” in Indio. While many in Indio saw cause to celebrate their welcoming attitudes towards the influx of trainees, clearly they were not welcoming to all.

White soldiers relax at the Indio USO in June 1942. Black soldiers were segregated to subpar USO facilities, though the local black community worked hard to provide entertainment and recreation space for the troops. U.S. Army photography, courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum.

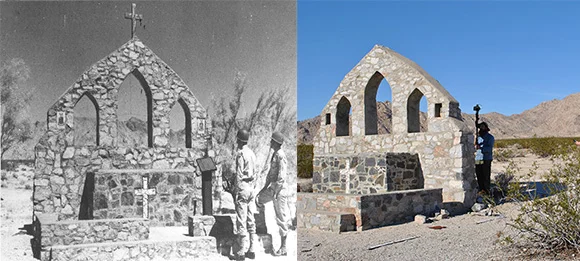

As the war progressed the majority of U.S. troops had already found their way oversees and the DTC (by then known as CAMA) closed to training on April 30, 1944, just 25 months after its inception. African American troops supervised the closure and Italian prisoners of war housed in the area worked to find and remove unexploded ammunition, though the DTC/CAMA’s size made additional removal of unexploded ordinances necessary in the 1950s and 1970s. With material shortages and rationing stateside, the military removed and reused what could be salvaged from the camps. Today, few architectural structures remain at the DTC/CAMA. Though the desert is slowly reclaiming them, concrete foundations, airstrips, and rock lined pathways are still visible. Two camps, Camp Coxcomb and Camp Iron Mountain still boast concrete relief maps used in training and original outdoor chapels. Eventually the landscape was again used in military training; in 1964 the armed forced held Joint Exercise Desert Strike, the largest maneuver training since World War II, within the boundaries of the former CAMA. As the United States engaged in more desert warfare towards the end of the 20th century, desert training areas like the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center Twentynine Palms and the Fort Irwin National Training Center assumed similar roles of the Desert Training Center, on a much smaller scale.

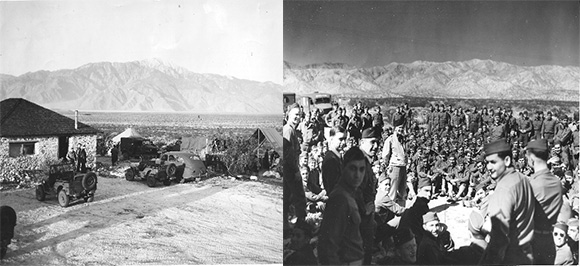

Few permanent structures were constructed at the DTC, even wooden framed ones were designed to be temporary. Camp Young, which served as the DTC headquarters, housed a few of these structures, though they were torn down quickly after the war. Note the canvas tents to the left; these were far more common at the divisional camps. U.S. Army photograph, courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum.

The outdoor chapel at Camp Iron Mountain is one of the few structures that remains. Left, photograph by Bill Threatt, courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum. Right, Bureau of Land Management Staff survey the remains of the Iron Mountain Chapel, courtesy of the Bureau of Land Management, Needles Field Office

The Bureau of Land Management oversaw the land shortly after the war and their initial push to preserve the camps and interpret the stories left behind resulted in the monuments, archives, and exhibits now dotting the landscape today. The General Patton Memorial Museum, opened in 1988, preserving the story of the Desert Training Center, but most specifically Camp Young, just a stone’s throw from the museum’s location in Chiriaco Summit. While the Patton Museum remains a private enterprise supported largely by donations and volunteers, the BLM too continues to preserve the wider expanse of land that fell within DTC/ CAMA confines. In February 2015, for example, the BLM used drone technology to survey the existing camp sites so that they could better document and preserve the structures and fading memories still left. The hope is that the area can be listed on the National Register of Historic Places before the last veteran who served at the DTC passes away. Though only 12% of the Desert Training Center has been archeologically surveyed, what remains reminds us of a time when over a million men made their way to the deserts of Southern California to prepare for battle a world away.ix

The Bureau of Land Management recently utilized drones to survey some of the DTC camps. Left, one of the BLM Drones prepares to complete an aerial survey. Right, an aerial view of the chapel at Iron Mountain, pictured above. Aerial surveying allows the BLM to record current conditions of archeological sites and note building foundations and even smaller objects, many of which have been lost when people take artifacts from the area, despite laws against removing such items. Courtesy of the Bureau of Land Management, Needles Field Office.

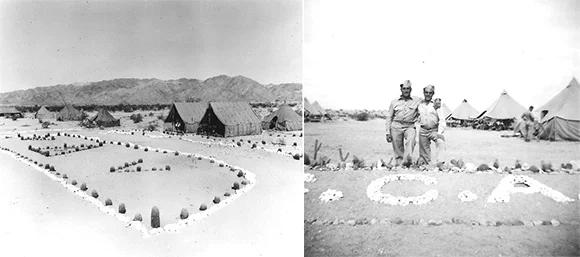

Troops often used rocks to line walkways or reproduce their insignias at the divisional camps. Left, cactus and rocks form Vs for the 5th Armored Division. U.S. Army photograph. Right, soldiers pose in front of a similar installation. Both courtesy of the General Patton Memorial Museum. Below some of the rock pathways and designs are still visible today. Courtesy of the Bureau of Land Management, Needles Field Office.

In the 1980s the BLM asked soldiers who served in the Desert Training Center to record their memories and experiences. Correspondence poured in from around the nation. Here a Walter Hennessey recalls his time at the Desert Training Center and how it prepared him for combat in North Africa. Courtesy of the Bureau of Land Management, Needles Field Office.

NOTES: iBill Davidson, “Desert Warfare: America Trains a New Kind of Army,” Yank, September 23, 1942, 5.

iiKatherine Ainsworth, The Man Who Captured Sunshine (Palm Springs: Etc Publications, 1978).

iiiColonel E. W. Pitburn quoted in “Desert Training Center Exhibit,” General Patton Memorial Museum, 62-510 Chiriaco Rd. Chiriaco Summit, California, November 2014.

ivMatt C. Bischoff, The Desert Training Center/ California-Arizona Maneuver Area, 1942-1944: Historical and Archaeological Context (Tucson: Statistical Research, 2000), 10.

vIbid.

viOne soldier recalled that the army investigated the heat related deaths of nearly 200 men training on U.S. soil. Weldon F. Heald, “With Patton on Desert Maneuvers,” Desert Magazine, July 1960, 24.

viiSidney L. Meller, The Desert Training Center and C-AMA: Study No. 15 (Washington: Historical Section of the Army Ground Forces, 1946), 30.

viiiIbid.

ixThe author would like to thank Christopher Dalu at the Bureau of Land Management and the General George Patton Jr. Memorial Museum for their assistance. Research on the Desert Training Center and CAMA was compiled from the following: Matt C. Bischoff, The Desert Training Center/ California-Arizona Maneuver Area, 1942-1944: Historical and Archaeological Context (Tucson: Statistical Research, 2000); California Desert District, Bureau of Land Management, Desert Training Center California-Arizona Maneuver Area, Interpretive Plan (Riverside: California Desert District, Bureau of Land Management, 1985); George W. Howard, “Desert Training Center/ California-Arizona Maneuver Area,” Journal of Arizona History 26, no. 3 (Autumn 1985): 273-294; Indio News, 1942-1944; Sidney L. Meller, The Desert Training Center and C-AMA: Study No. 15 (Historical Section: Army Ground Forces, 1946). For more information see the following websites: Desert Training Center Sky Trail http://skytrail.info/new/home.htm and Desert Training Center http://www.deserttrainingcenter.com/.