In August 1939, just a few days before the German invasion of Poland, Time magazine reprinted the words of the Nazi geographer Ewald Banse: "War...is above all things a geographical phenomenon. It is tied to the surface of the earth; it derives its material sustenance from it, and moves purposefully over it...."i Yet for the majority of Americans at the time, the war was advancing not in real space, but on the pages of their newspapers and magazines, in the waves of radio addresses, and in the letters of their loved ones, fighting overseas. In the face of the global war and its destruction, images of landscape became as much of a contested ground as the land itself, not only visualizing the progress of the war, but also embodying and challenging war-time national ideology and international policy. I present below a brief overview of major trends in cartography and topography during the 1940s, which aims not only to uncover the specifics of wartime geographical imagination, but also to provide some historical context for understanding our own conception of global space and its symbolic representation.

In 1943, cartographer Helmuth Bay commented on the growing interest in world geography among regular Americans, remarking that:

...with a global war in progress and American fighting men stationed in more than fifty countries or colonies,... all about us people are tossing about such names as Guadalcanal, Attu, Pantelleria, and other tiny places with the greatest of ease and familiarity, while in restaurants we find armchair strategists capable of sketching very credible maps of the Soviet Union on napkins and even spelling such names as Dnepropetrovsk and Simferopol correctly.ii

As Bay's statement attests, during World War II, the American public became increasingly concerned with international relations, a trend that marked a significant departure from the preceding two decades of isolationism and prevalent geographical indifference. With the outbreak of the war, popular geography quickly became an integral part of everyday life, highlighting the new-found importance of topographical tools used for visualizing the U.S. involvement in global affairs. For instance, in a 1942 radio address, President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked his listeners to "spread before you the map of the whole earth, and to follow with me the references which I shall make to the world-encircling battle lines of this war...We must all understand, face the hard fact, that our job now is to fight at distances which extend all the way around the globe."iii In preparation for the broadcast, Los Angeles Times published a map of the world to be used in conjunction with the President's address (Figure 1).iv With the headline reading "Here's Your Map...," editors emphasized the importance of everyone's participation on the homefront and aimed to bring the reality of the war closer to every American household. In a similar gesture, starting in 1942, The New York Post published weekly maps of different geographic areas, which were designed to be used while listening to the news on the radio, so that Americans could "visualize as well as hear place names in which world history is being made (Figure 2)."v Early steps in the effort to re-educate Americans in world geography, these occurrences marked a wartime shift in territorial visuality and geographical imagination, ushering in a new global consciousness.vi

Figure 1 Here's Your Map

Figure 2 Map news 1942

In addition to visualizing the progress of the war, period maps also embodied the unfolding drama of the news, transmitting its emotional intensity. Just three weeks after the American entry into the war, Life published a two-page map of the globe that outlined recent developments on all fronts of the war (Figure 3). With the sharp contrast between white arrows, marking the recent movements of Allied armies, and the ominous black pools of the Axis territories and recent conquests, the map is clearly divided between the two forces at war, their influence reaching far beyond national borders. The thick diagonals of arrows and dotted lines connect various sites and areas across the globe, further highlighting the perilous and constantly shifting equilibrium of power and territorial control. It is at the points where black and white lines collide, almost touching each other, that we are invited to imagine the horror of the war, its battlefields with scorched earth and dying soldiers. The article’s dramatic language echoes the heavy dynamism of the map, spelling out the desired emotional effect of the imagery: “The black arrows in Russia turn on themselves and head backward. On the frigid ground beneath these arrows, German soldiers were freezing to the earth when they lay down for cover.”vii It is important to note that the map locates the U.S. at the center, in the space between the two facing pages, with the rest of the world unfolding on both sides. This visual arrangement not only acknowledges the privileged position of the magazine’s audience as they look at the map, but also symbolically places the U.S. at the center of world affairs. A similar message is made explicit in the map that appeared in Los Angeles Times on June 27, 1942 with the heading “America, in Center of World at War…” (Figure 4).viii

Figure 3 Whole Globe a Battlefield

Figure 4 America in Center of World

Published in 1941-42, these early war maps utilize the conventional Mercator projection, which translates the earth’s spherical surface on a two-dimensional grid of evenly-spaced, strictly perpendicular meridians and parallels.ix Yet with topographic imagery becoming a common feature of visual landscape during World War II, a number of geographers and cartographers challenged the dominance of the Equator-based Mercator projection, instead arguing in favor of “globe” maps, which focused on earth’s sphericity, continuity, and unity.x Thus, an article in Life magazine from August 1942 presented Americans with world maps that showed the globe in terms of relationships and aerial routes, rather than the traditional categories of separate continents and hemispheres (Figure 5).xi Closely linked to the contemporaneous policy shift from isolationism to global engagement, this mode of representation emphasized the importance of aerial travel for international relations and U.S. wartime strategy, marking a turn to what historian Alan Henrikson has termed “air-age globalism.”xii Allowing for a degree of distortion in scale and proportions, the period “globe” maps were primarily concerned with representing the earth’s navigable potential, for as a wartime observer put it in 1944, “space alone has no significance… it is mobility in space that gives it meaning.”xiii

Figure 5 MapsGlobal War Teaches Global Cartography

The work of Richard Edes Harrison, whose maps were published regularly during the war in Fortune magazine and in 1944 as an atlas, entitled Look at the World, is another striking example of this turn toward a new territorial visuality. In his description of a polar projection map “One World, One War,” Harrison highlighted the importance of alternative cartographic approaches to representing the global war: “It is a map of the problems and opportunities of fighting all over the world at once. While it includes obvious distortions, which increase toward the south, it… is a continuous map that shows the world in one unbroken piece” (Figure 6).xiv Look at the World also contained a number of so-called “perspective” maps, which in their oblique angles resembled photographs taken from an elevated position (Figure 7).xv In her comprehensive analysis of Harrison’s work, historian Susan Schulten has persuasively demonstrated the innovative quality of these maps, which aimed to visualize strategic relationships between individual nations, as well as the network of travel and supply routes between different fronts of the war.xvi

Figure 6 Harrison, One World, One War

Figure 7 Harrison, Europe from the East

Maps published in Los Angeles Times throughout the war reveal a similar progression from the conventional Mercator projection to more engaging modes of cartographic representation. For instance, the work of cartographer Charles Owens, published in the newspaper regularly during the war, represents a distinct style of “collage-cartography” (Figures 8-9).xvii Seamlessly shifting between scales and different perspectives, Owens’s maps combine geographic outlines of islands and continents with scenes of local landscape and images of war action. In their detailed analysis of Owens’s work, scholars Denis E. Cosgrove and Veronica della Dora have noted a dramatic, almost cinematic quality of his maps, which not only visualize the progress of the war, but also create an unmitigated point of encounter between the viewer and the reality of the battlefield.xviii This attempt to bridge the distance between home and the war abroad is highlighted in Owens’s map of Solomon Islands published on August 16, 1942, in which the depiction of islands in Oceania is overlaid by an outline of California to serve as a comparison of scale and distance (Figure 10).

Figure 8 The War Week Feb 21

Figure 9 The War Week, Dec 13

Figure 10 The War Week, Aug 16

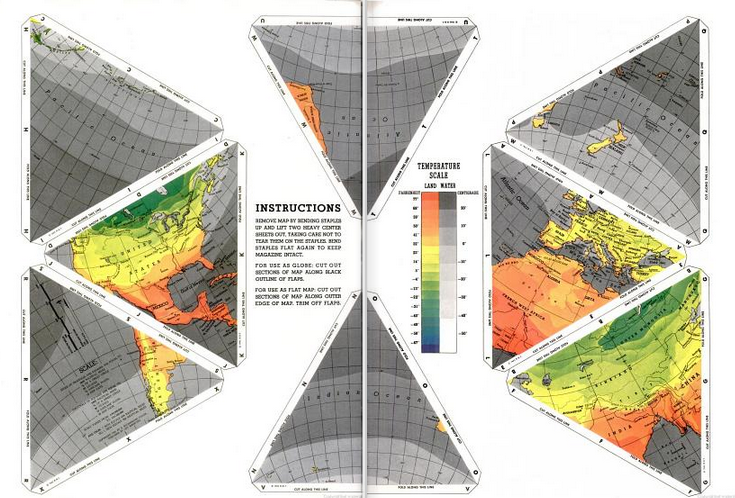

A similar focus on fragmentation, on disintegration and reassemblement of topographic surface is highlighted in Life’s feature on the Dymaxion map from 1943 that included a color version of Dymaxion globe, which readers were invited to cut out and assemble for their personal use (Frontpiece, Figure 11).xix According to the article, the fourteen individual segments—eight triangles and six squares—could be compiled into a three-dimensional approximation of a globe or “laid out as a flat map, with which the world may be fitted together and rearranged to illuminate special aspects of its geography.”xx The readers were also offered a number of possibilities on how to assemble the elements, depending on whether one wanted to visualize the boundaries of the British Empire or to understand the geographical impulse behind the Japanese imperial ambition (Figure 12). In either case, the process involved imagining the surface of the globe as a compilation of parts that exist in relation to each other, a kaleidoscope of colorful details that acquire meaning only when arranged into a whole.

Figure 11 Dymaxion map

Figure 12 Dymaxion map

Simultaneously playful and violent in its radical disintegration of the earth’s surface, the Dymaxion map serves as a powerful metaphor for its contemporary moment, capturing a geographical discourse built on the idea of intellectual dominion over the global space and a desire to grasp its interconnectedness and unity. In this didactic object, as well as in the images discussed above, the act of fragmentation and redistribution of topographical surface lends itself to exploration about the nature of cartographic representation and its place within visual culture. Dynamic and visually engaging, these historic maps provide a context for understanding our own geographical imagination, shaped by Google maps and other similar programs with their propensity for the long zoom, navigable potential, and ability to always track the user’s current location within both real and cartographic space.

NOTES:

i “Europe: The Geography of Battle,” Time, 28 August 1939, 26.

ii Helmuth Bay, “War News via Maps,” Wilson Library Bulletin 18 (November 1943): 221.

iii “Report on the Military and Strategic Course of the War,” Radio address to the nation, 23 February 1942; rpt. in The War Messages of Franklin D. Roosevelt, December 8, 1941, to October 12, 1942 (Washington, D.C.: Published by the United States of America, 1942), 40.

iv“Here’s Your Map of the World to Use While Listening to President Roosevelt Tonight,” Los Angeles Times, 23 February, 1942, B.

v“Map News with Post on WQXR Tonight,” New York Post, 6 June 1942, 17.

viFor a detailed discussion of the cartographic revolution during the war, see Susan Schulten, The Geographical Imagination in America, 1880-1950 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 204-238.

vii“Whole Globe a Battlefield,” Life, 29 December 1941, 32.

viii“America, in Center of World at War, Fights Battle of Distance and Supply on Many Fronts,” Los Angeles Times, 27 June, 1942, 16.

ixUsed since 1569, the Mercator map is particularly useful for navigating between points and mapping smaller units of topographical space, such as cities and streets (which explains in part its use by such programs as Google maps). However, the Mercator map is characterized by a high level of distortion in representing larger topographical units, such as continents, with the scale gradually increasing toward the North and South poles. This can be observed in Google maps, when scrolling vertically on the same level of zoom, with the scale market in the lower right corner of the screen visibly increasing as one gets further away from the Equator.

xFor a detailed discussion of the cartographic revolution during the war, see Susan Schulten, The Geographical Imagination in America, 1880-1950 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 204-238.

xi“Maps: Global War Teaches Global Cartography.” Life, 3 August 1942, 7.

xiiSee Alan K. Henrikson, “The Map as an Idea: The Role of Cartographic Imagery during the Second World War” The American Cartographer 2 (1975): 19-53.

xiiiJames C. Malin, “Space and History: Reflections on the Closed-Space Doctrines of Turner and Mackinder and the Challenge of Those Ideas by the Air Age,” Agricultural History 18 (April and July 1944): 107.

xivRichard Edes Harrison, Look at the World: The Fortune Atlas for World Strategy (New York, N.Y.: A. A. Knopf, 1944), 9.

xv“Perspective Maps: Harrison Atlas Gives Fresh New Look to Old World,” Life (February 28, 1944): 56-61.

xviSusan Schulten, “Richard Edes Harrison and the Challenge to American Cartography,” Imago Mundi 50 (1998): 174-188.

xviiDenis E. Cosgrove and Veronica della Dora, “Mapping Global War: Los Angeles, the Pacific, and Charles Owens’s Pictorial Cartography,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 95, no. 2 (June 2005): 373.

xviiiIbid, 373-390.

xix“Life Presents: R.Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion World,” Life, 1 March 1943, 41-55.

xxIbid, 41.